2018—2024

An experiment in the techniques of awakening

Ignota Diary 2024

Created by Sarah Shin and Ben Vickers

Edited by Sarah Shin and Jay Drinkall

Designed by Cecilia Serafini

The Ignota Diary is a tool for discovery in the practice of everyday life.

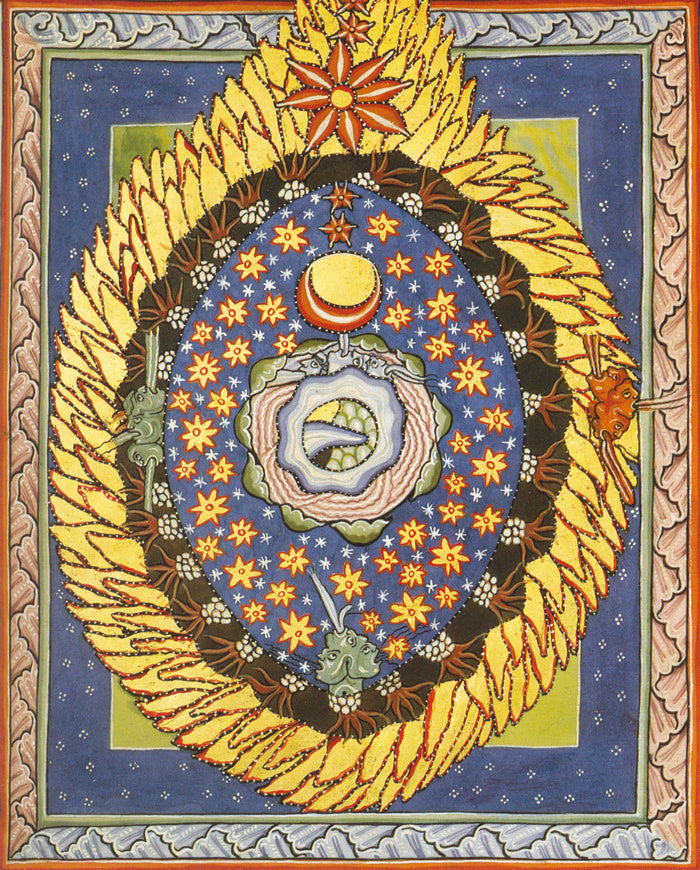

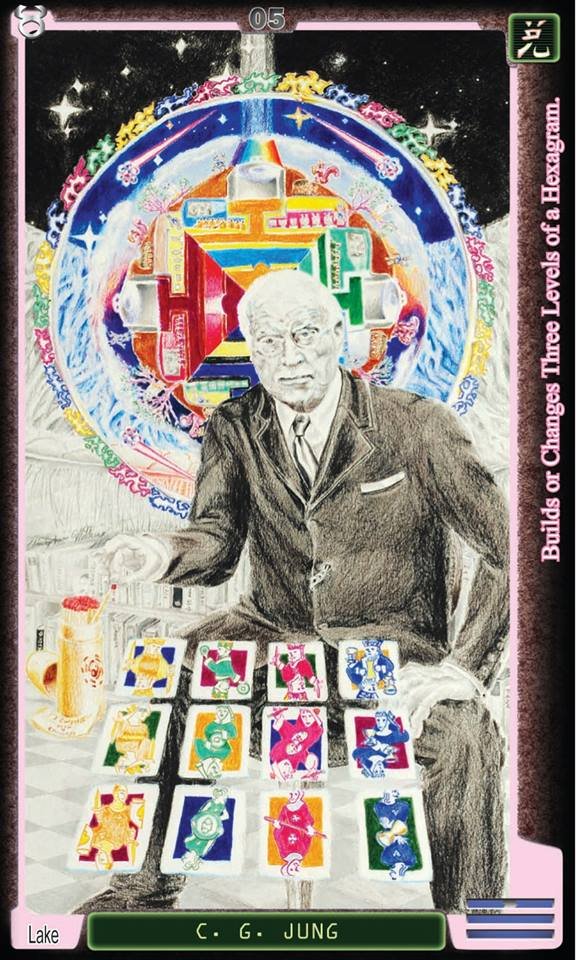

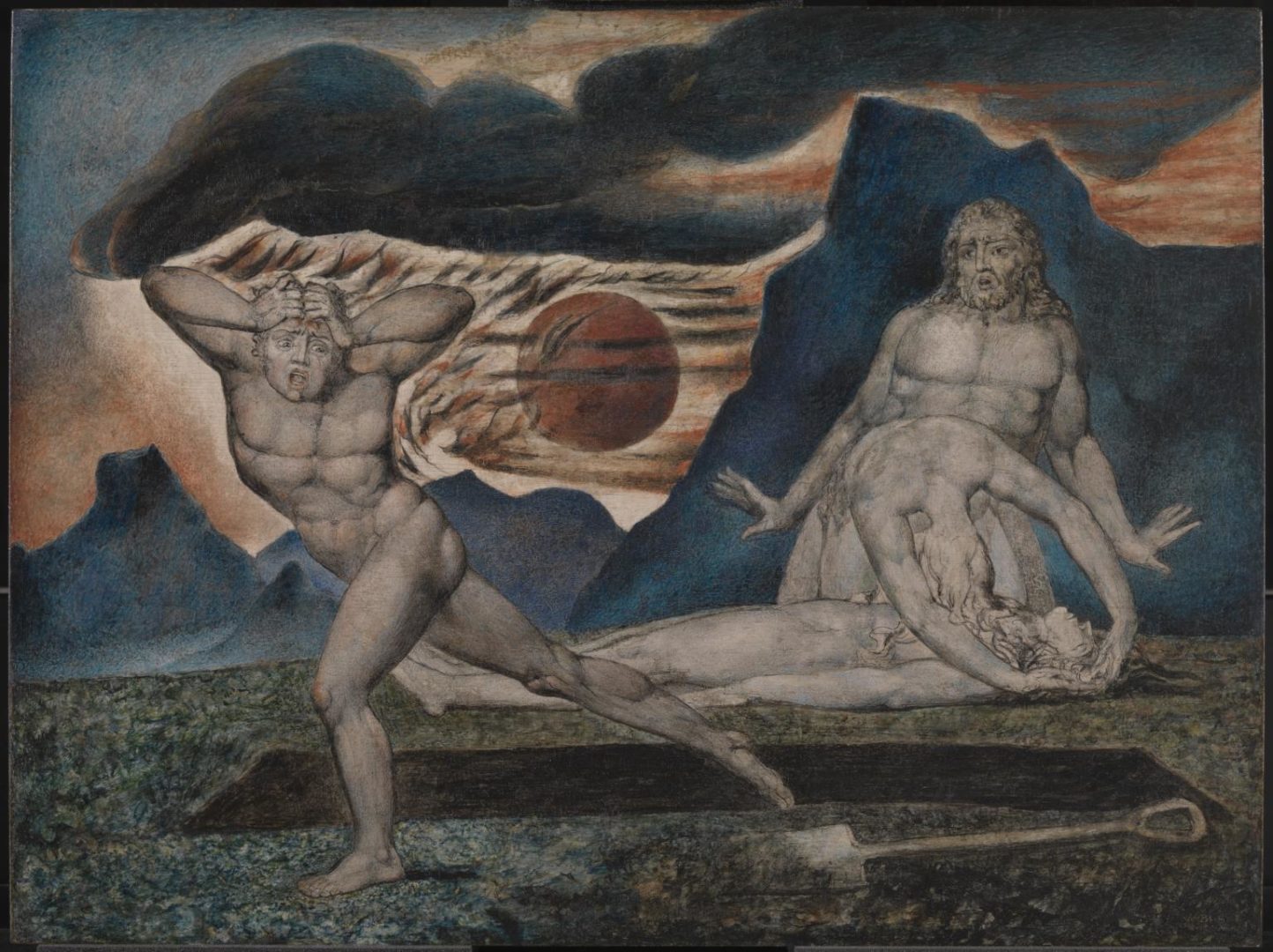

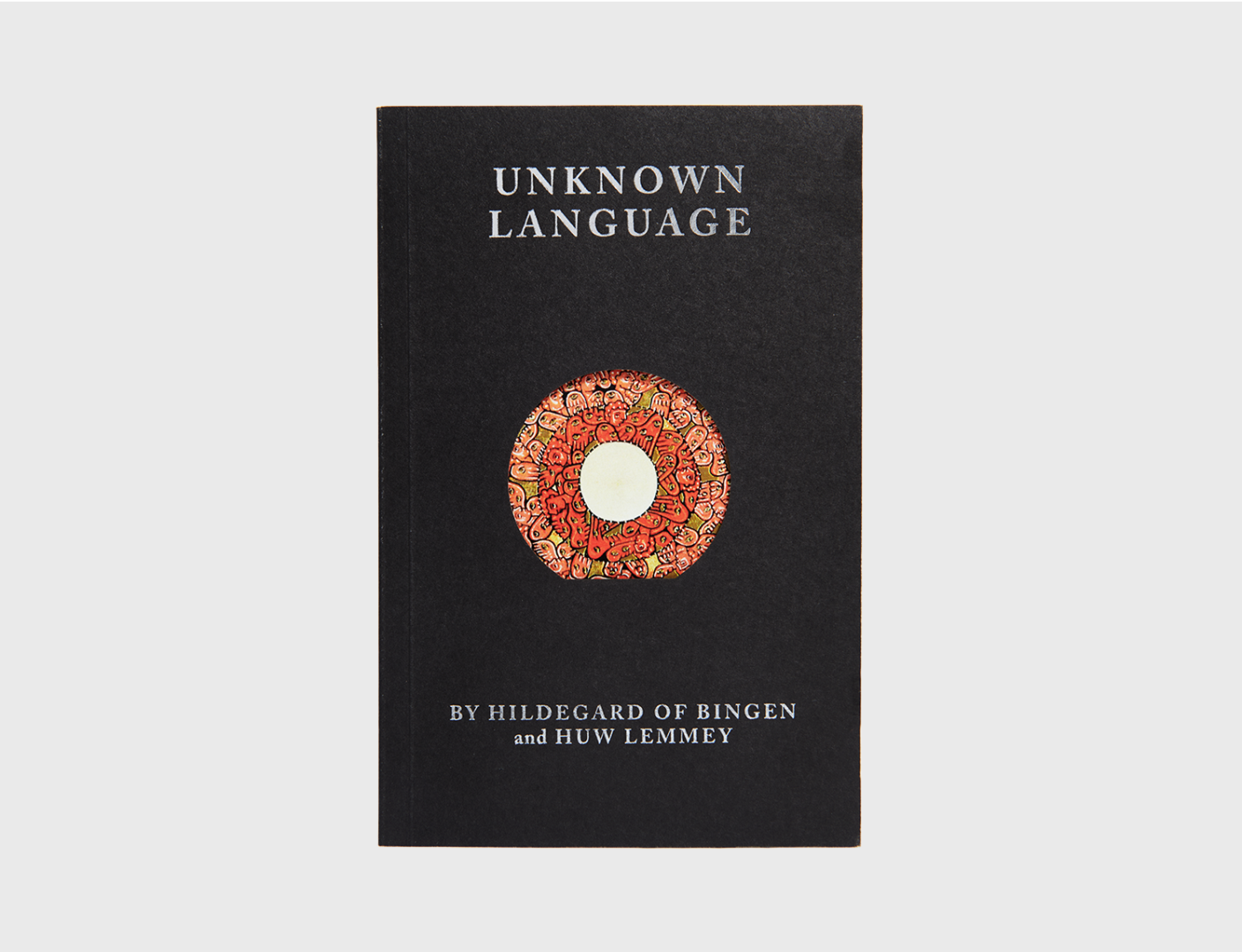

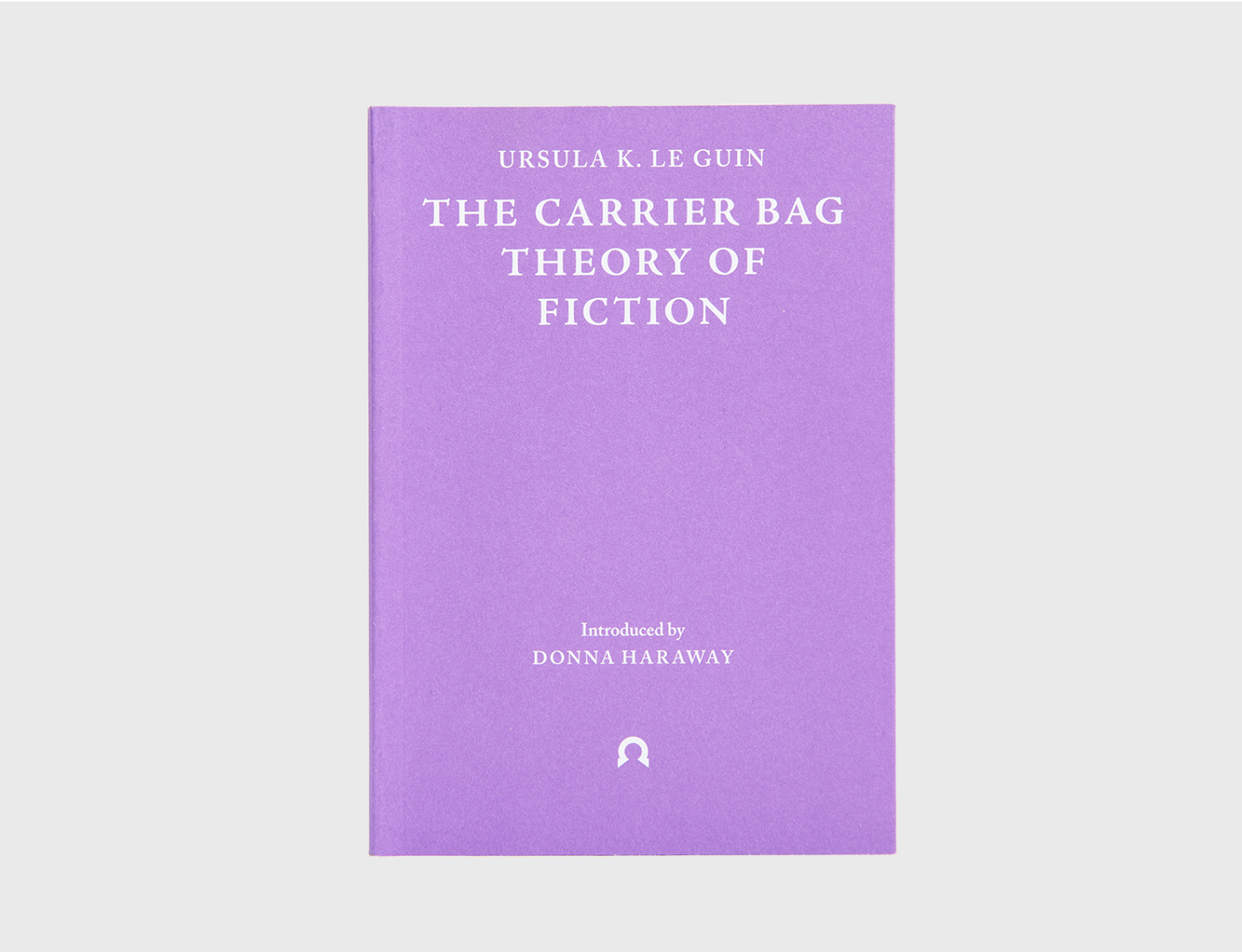

This beautifully designed diary and week-to-view planner is filled with historically significant magical and sacred dates from around the world. Drawn from events such as the Buddha’s birthday, esoteric festivals and artistic and occult history, the diary touches on the lives of characters such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Ithell Colquhoun, Zora Neale Hurston, Carl Jung, Simone Weil, Leonora Carrington, Maya Deren, Aleister Crowley, George Bataille, Timothy Leary, Hilma af Klint, Saint Hildegard of Bingen, William Blake, W.B. Yeats and Octavia Butler.

The diary provides full astrological navigation for 2024 with an overview of the year by astrologer Gray Crawford, a birth chart template and guides to moon magic, houses, planets and symbols. A guide to key transits, retrogrades and lunar phases allows you to organise your life in alignment with the astrological weather. A global map showing sacred sites provides inspiration for transformative pilgrimages.

Rituals by artists Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Bhanu Kapil, Nisha Ramayya and Himali Singh Soin, and tarot spreads by adrienne maree brown, Sarah Faith Gottesdiener and Pam Grossman, offer guidance and space for reflection throughout the year. Additional sources of inspiration include guides to sonic meditation by Pauline Oliveros, sacred spaces by Leila Sadeghee, mushrooms by Ellen Percival, and spellcraft by Bones Tan-Jones, weather by Jay Drinkall and soji cleaning by Zen monk Shoukei Matsumoto, author of the bestseller A Monk’s Guide to a Clean House and Mind. To support a holistic approach to health and wellbeing, an appendix contains guides to sacred spaces, healing herbs, acupressure, kriya yoga and daily practice.

Contributors: Acupressure by Maria Christofi, Astrology by Gray Crawford, Herbal Remedies by Paige Emery, Kriya Yoga by Rachel Okimo, Korean Ink Illustrations by Jungran Kim, Mushroom Guide by Ellen Percival, Prayer Guide by K Allado-McDowell, Rituals by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Bhanu Kapil, Nisha Ramayya and Himali Singh Soin, Ritual Spaces by Leila Sadeghee, Seed Bombs by Jenna Sutela, Sonic Meditations by Pauline Oliveros, Spellcraft by Bones Tan-Jones, Tarot by adrienne maree brown, Sarah Faith Gottesdiener and Pam Grossman, Weather by Jay Drinkall.

Praying Hands Candles

Ideal for meditation and devotional practice, the Ignota x Croydon Candles Praying Hands Candles come in three scents:

- Frankincense (purple) for energetic purification, protection and enhancing intuition.

- Sandalwood (blue) for calming the mind, encouraging heart-opening and relaxation.

- Oud wood (black) for cultivating peace, inner strength and eliminating negative energies.

Specially commissioned by Ignota in a highly limited edition, these soy wax candles are individually handmade by Croydon Candles in London.

Resources for Palestine

Support the Palestinian people in their struggle for liberation – collected resources below.

DONATIONS

Médecins Sans Frontières

International Committee of the Red Cross

Medical Aid For Palestinians

Alliance For Middle East Peace

LETTERS

Sign the Mosaic Rooms letter calling for cultural organisations to show solidarity to Palestine

Sign the Artists for Palestine letter of solidarity

Email your MP (UK)

RESOURCES

Reading resources by Mosaic Rooms

Read STUART issue 2, digitised for free and hosted by Mosaic Rooms

Why to boycott the Zabludowicz, e-flux

Read the87press’s call to action for fellow NPOs

BOYCOTT AND DIVESTMENT ORGS

https://boycottzabludowicz.wordpress.com/

https://bdsmovement.net/

STRIKE

Ignota will join the global strike for Palestine on Friday, 20 October. Together with artists and other organisations, we will be closed and use this time to learn and reflect together in order to work for a better future for everyone. We encourage you to join in solidarity.

Ignota Gathering: The Spiral

St James’s Church Piccadilly, London

Friday 13 October 2023, 13:00-22:00.

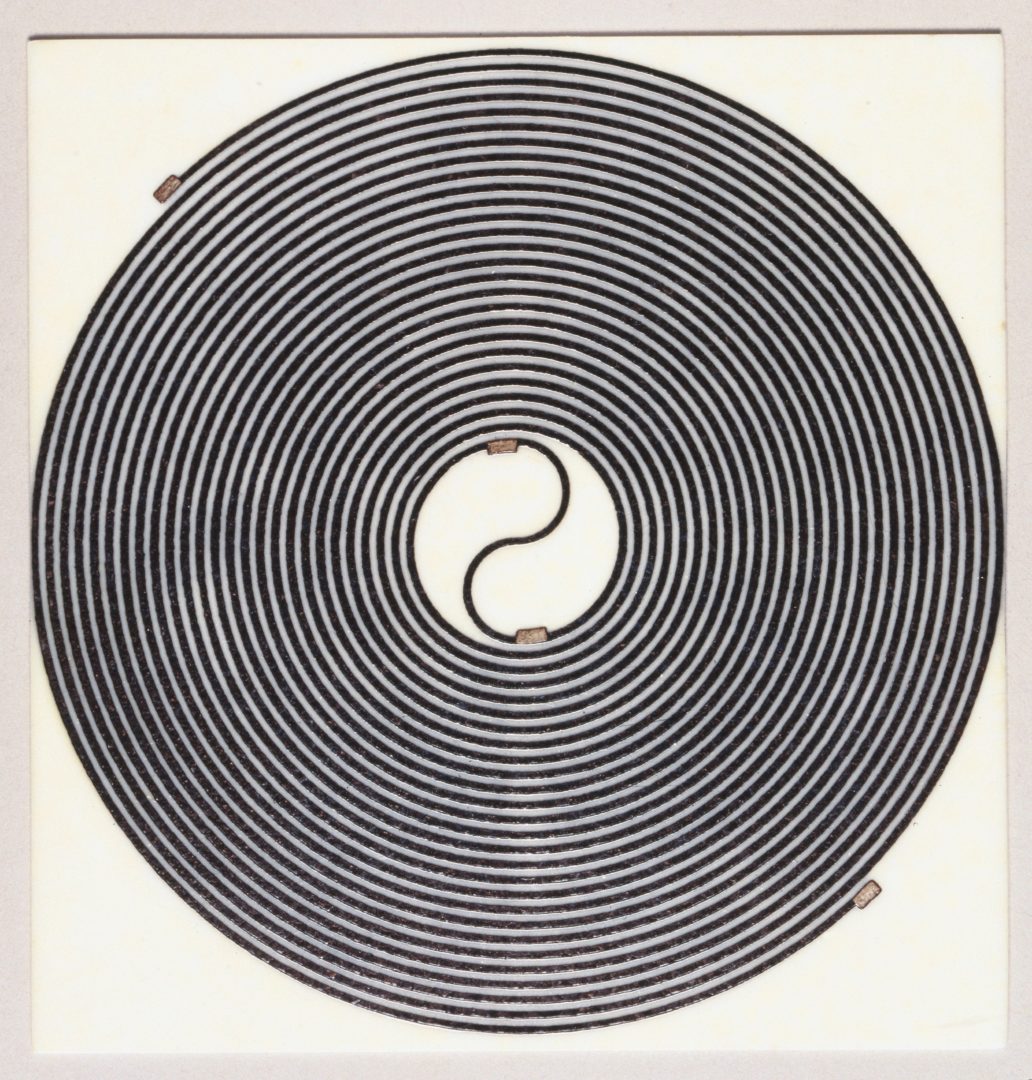

The Spiral is a turning, a gathering – a world in the making. A common pattern of nature – found across cosmic galaxies, snail shells, pine cones, flowers and DNA – the spiral symbolises the constant change and evolution of the universe. Spirals are also a structure of experience and memory: we learn and grow through repetition and return.

Join us at The Ignota Gathering: The Spiral to celebrate Ignota’s fifth birthday on Friday 13 October at St James’s Church, Piccadilly, London, with Ignota’s friends and family to explore the spiral through resonance, poetry and philosophy.

The day and evening will unfold across dialogues, collaborations and performances spiralling around psychedelic hieroglyphs, Hilma af Klint’s imagery and the spirit realm, cinematic whorls, the Endcore doom- and downward- spiral into Horny-Sad Hell, eternity and ornament, open-ended languages and more.

‘True journey is return.’ – Ursula K. Le Guin

With Shumon Basar, Federico Campagna, Jennifer Higgie, Bones Tan Jones, Bhanu Kapil, Paul Purgas, Nisha Ramayya, Himali Singh Soin, Tzekin and Flora Yin Wong for the afternoon.

And Lucinda Chua, NYX, Tai Shani and Maxwell Sterling for the evening.

Programmed by Sarah Shin and Susanna Davies-Crook.

Supported by the ICA London and SJP.

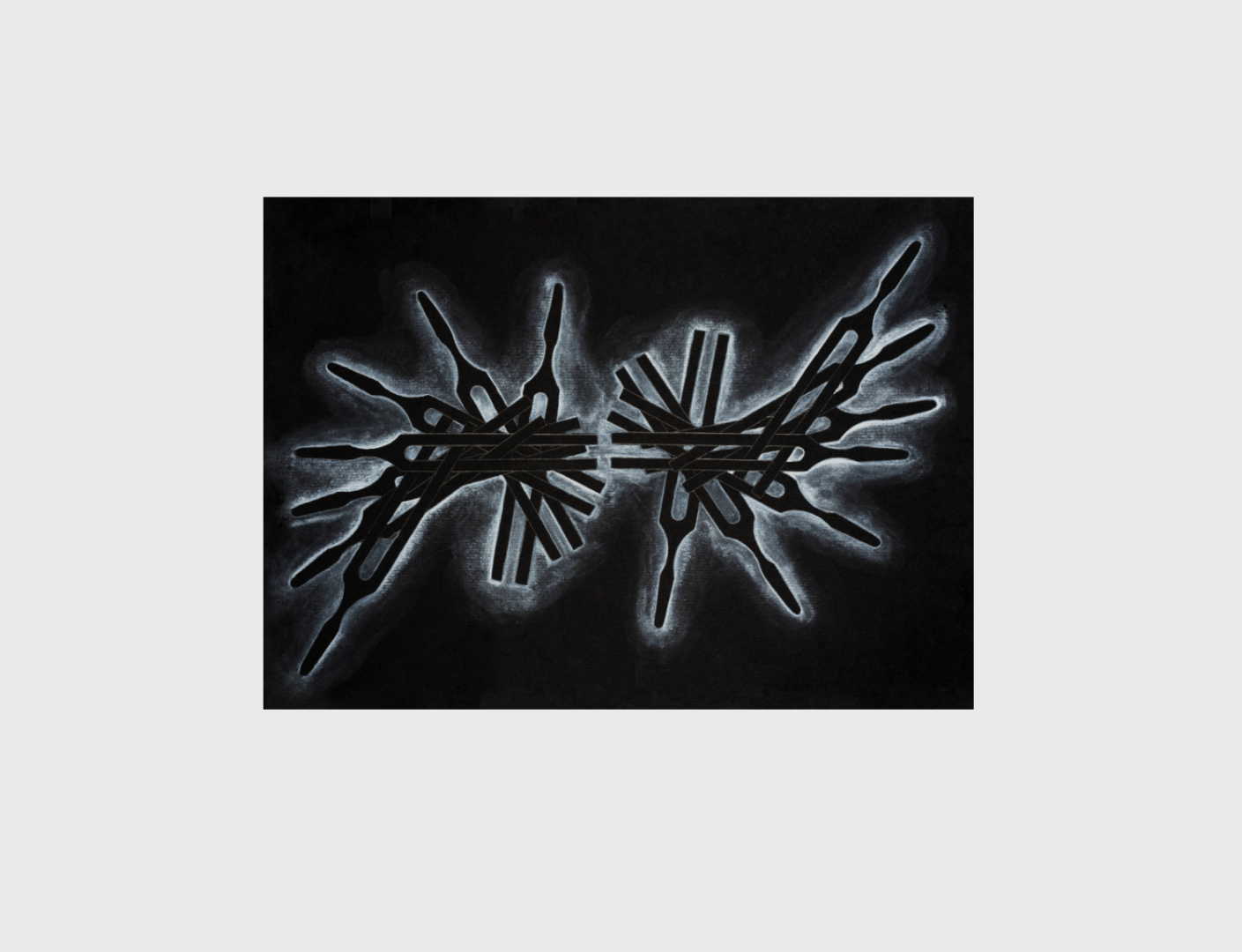

Aura Satz Spell Cards

‘Our world is a complex matrix of vibrating energy, matter and air, just as we are made of vibrations. Vibration connects us with all beings and connects us to all things interdependently.’ – Pauline Oliveros

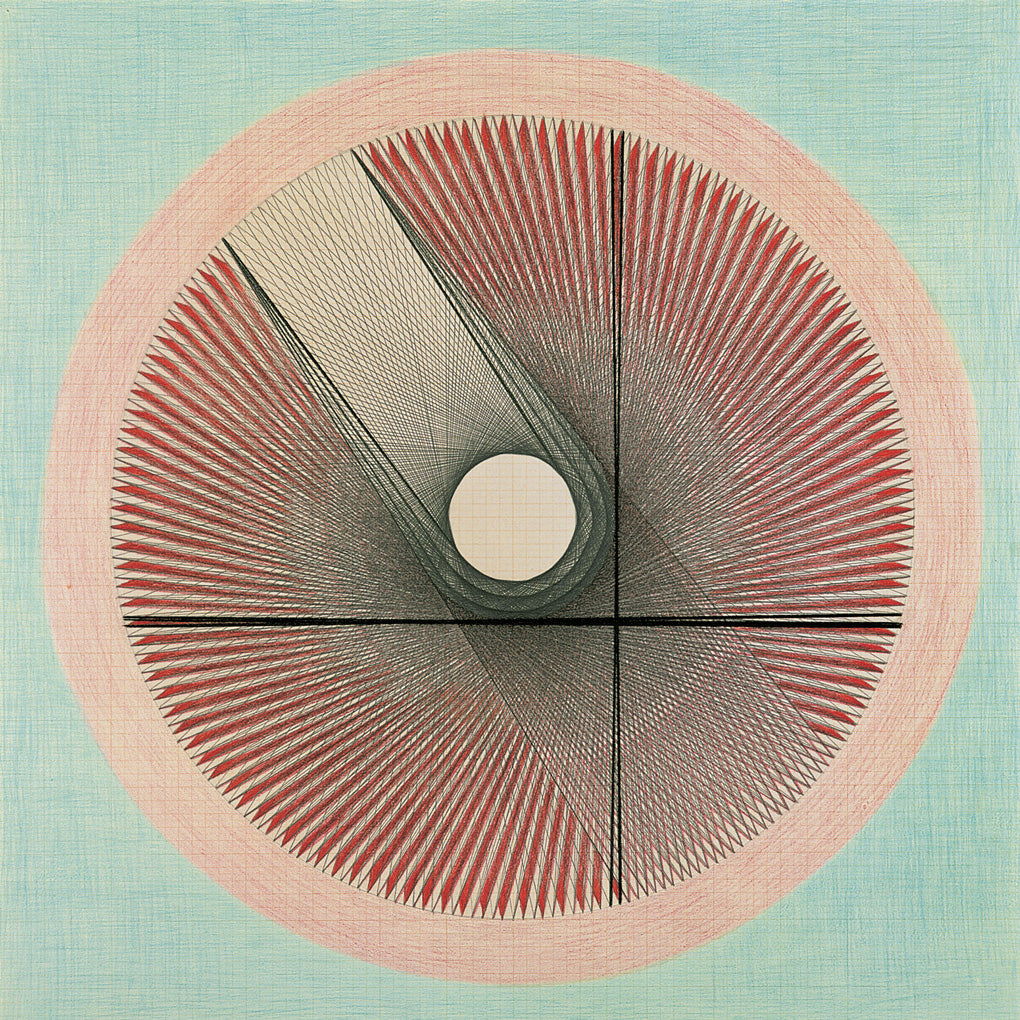

For the publication of Quantum Listening by Pauline Oliveros, artist Aura Satz has created Tuning Fork Spells, a series of drawings made through a meditative process of attention and attunement.

- 105 x 148mm

- Fine print on thick paper

- Each spell card includes a Deep Listening quote by Pauline Oliveros on the reverse

Reading Gaia

With Josh Appignanesi, Buzz Baum and Anouschka Grouse

Tuesday 12 September, Reference Point, 180 Strand, London

In this reading group and talk, we read Gaia and Philosophy by Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan (Ignota, 2023) and explore what Gaian ideas of interdependence, collaboration and symbiosis offer for life on Earth.

After reading from the text, filmmaker Josh Appignanesi discuss Gaia theory through the lens of activism alongside Buzz Baum from the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Cell Biology and psychoanalyst and writer Anouchka Grose. Josh’s new film My Extinction asks: What does it take for us to act on the climate crisis – especially if we’re the kind of person who should already be acting?

Gaia describes a living Earth, an idea with precedents in natural science and philosophy for 2,500 years, and longer in many indigenous belief systems. If the Gaia hypothesis has provided a basis for a new ecology, connected to rich world-views, how can we effect real change for the future of our planet? What are the alternatives to failing systems underpinned by greed and short-termism?

Gaian Worlds

Unsound Festival, Krakow, Poland

At Unsound 2023, Ignota presents three journeys by Susanna Davies-Crook, Lyra Pramuk and Sarah Shin as a planet in the form of a body, a body in the form of a planet. These journeys take the forms of sonic choreographies, games and enquiries to explore the boundary between the internal and external. Traversing this world-skin – coming together and coming apart – they challenge the illusion of separation between individuation and collaboration, self and other.

Gaian Ecologies

17 September 2023, 14:00–19:00

Camden Arts Centre Garden, London

‘Gaia Season: A Body in the Form of a Planet’ celebrates Gaia theory and the influence of interdisciplinary biologist Lynn Margulis’ life and work.

On this day of active research in the garden, artists, speakers and gardeners lead journeys and enquiries into organisms, slime trails and compost, and expanded ways of looking at life. Knee-deep in swamps and water, pulling up clumps of mud and silt, Margulis studied the microbial in order to understand Gaia as a whole. Ignota’s Gaia season echoes Margulis’ methods of hypothesis and experimentation to dig into the theories of Gaia and the practice of examining life on Earth.

Confirmed artists and speakers include Tamara Henderson, Taey Iohe, Tom Jeffreys, Harun Morrison, Himali Singh Soin, Wild Alchemy Lab, and more to be announced.

Programmed by Susanna Davies-Crook and Sarah Shin.

Image: Bloom by Sammy Lee.

As Above, So Below: Gaia – The Story of Science

22 April 2023, 11:30 BST

Science Gallery, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9GU

With Sougwen Chung, Asad Raza and Gary Zhexi Zhang.

What are the legacies and utilities of Gaia theory within today’s art, culture, technology and society? In this panel discussion, artists, technologists, curators and scientists reflect on the influence of Gaia theory on contemporary ideas and practices of collaboration, mutualism and sustainability. What new models of living can be developed that prioritise ecological stewardship and economic redistribution? How do Gaian ideas support human and other-than-human creativity and explorations of consciousness?

This panel discussion took place as part of AS ABOVE, SO BELOW. The event, coinciding with the launch of Gaia and Philosophy, draws inspiration from Lynn Margulis’ creative scientific vision to illuminate the interconnectedness of life, from microbial to planetary bodies. Taking place in the context of the climate emergency and coinciding with the publication of Gaia and Philosophy by Margulis and Dorion Sagan (Ignota, 2023), the programme explores the importance of Gaia theory – not only for understanding the emergence of past life and interconnectedness of human and other-than-human existence today, but to ask what possibilities Gaia offers for shaping our future.

Curated by Sarah Shin, co-founder of Ignota Books, in collaboration with Gaia Art Foundation and Science Gallery London. Media Partner: Tank. Video courtesy Science Gallery London.

As Above, So Below: Gaia Today

22 April 2023, 11:30 BST

Science Gallery, Great Maze Pond, London SE1 9GU

With Edna Bonhomme, Daisy Hildyard, Merlin Sheldrake and Gaia Vince.

Gaia theory has inspired scientific and cultural narratives that highlight the interdependence of humans and the natural world. Drawing on biology, environmental science, climate and histories and languages of science, the panellists will explore Gaia theory as a form of scientific storytelling that weaves together different disciplines and connects them to a profound narrative about the Earth’s history and future. What is the role of science in society? What kinds of storytelling allow us to hold many sciences together at the same time?

This panel discussion took place as part of AS ABOVE, SO BELOW. The event, coinciding with the launch of Gaia and Philosophy, draws inspiration from Lynn Margulis’ creative scientific vision to illuminate the interconnectedness of life, from microbial to planetary bodies. Taking place in the context of the climate emergency and coinciding with the publication of Gaia and Philosophy by Margulis and Dorion Sagan (Ignota, 2023), the programme explores the importance of Gaia theory – not only for understanding the emergence of past life and interconnectedness of human and other-than-human existence today, but to ask what possibilities Gaia offers for shaping our future.

Curated by Sarah Shin, co-founder of Ignota Books, in collaboration with Gaia Art Foundation and Science Gallery London. Media Partner: Tank. Video courtesy Science Gallery London.

As Above, So Below

In the 1970s, microbiologist Lynn Margulis and atmospheric chemist James Lovelock developed the Gaia theory. Embracing the circular logic of life and engineering systems, the Gaia theory states that Earth is a self-regulating complex system in which life interacts with and eventually becomes its own environment. Gaia, describing a living Earth – a body in the form of a planet – resonates with the ancient magico-religious understanding that all is one: as above, so below.

AS ABOVE, SO BELOW draws inspiration from Lynn Margulis’ creative scientific vision to illuminate the interconnectedness of life, from microbial to planetary bodies. Taking place in the context of the climate emergency and coinciding with the publication of Gaia and Philosophy by Margulis and Dorion Sagan (Ignota, 2023), the programme explores the importance of Gaia theory — not only for understanding the emergence of past life and interconnectedness of human and other-than-human existence today, but to ask what possibilities Gaia offers for shaping our future.

SCHEDULE

Friday 21 April

18:45: Doors open

19:00 – 21:30: Screening of Symbiotic Earth (Theatre)

AR by Sammy Lee in Atrium

Symbiotic Earth: How Lynn Margulis rocked the boat and started a scientific revolution

Symbiotic Earth explores the life and ideas of scientific rebel Lynn Margulis, who challenged entrenched theories of male-dominated science and caused a seismic shift in our understanding of life. Divided into ten discrete essays, the film explores how her vision of a symbiotic planet offers bold insights into health, society and nature, and inspires creative approaches to our pressing environmental and social crises.

Director: John Feldman, 2017, 2h 27m

Saturday 22 April

11.15 – 11.30: Introductions by Sarah Shin and Burcu Yuksel (Theatre)

11.30 – 12.30: Gaia – The Story of Science panel discussion (Theatre)

12:30 – 1.30: Break for lunch

13.30 – 14.30: Gaia Today panel discussion (Theatre)

14.45 – 15.45: Polymorphic Microbe Bodies Workshop (Workshop)

14.45 – 16.15: Artists’ film screenings (Theatre)

16.15 – 17.15: Poetry readings

AR by Sammy Lee in Atrium

PANEL DISCUSSIONS

Gaia: The Story of Science

Edna Bonhomme, Daisy Hildyard, Merlin Sheldrake and Gaia Vince.

Gaia theory has inspired scientific and cultural narratives that highlight the interdependence of humans and the natural world. Drawing on biology, environmental science, climate and histories and languages of science, the panellists will explore Gaia theory as a form of scientific storytelling that weaves together different disciplines and connects them to a profound narrative about the Earth’s history and future. What is the role of science in society? What kinds of storytelling allow us to hold many sciences together at the same time?

Gaia Today

Sougwen Chung, Asad Raza and Gary Zhexi Zhang.

What are the legacies and utilities of Gaia theory within today’s art, culture, technology and society? In this panel discussion, artists, technologists, curators and scientists reflect on the influence of Gaia theory on contemporary ideas and practices of collaboration, mutualism and sustainability. What new models of living can be developed that prioritise ecological stewardship and economic redistribution? How do Gaian ideas support human and other-than-human creativity and explorations of consciousness?

WORKSHOP

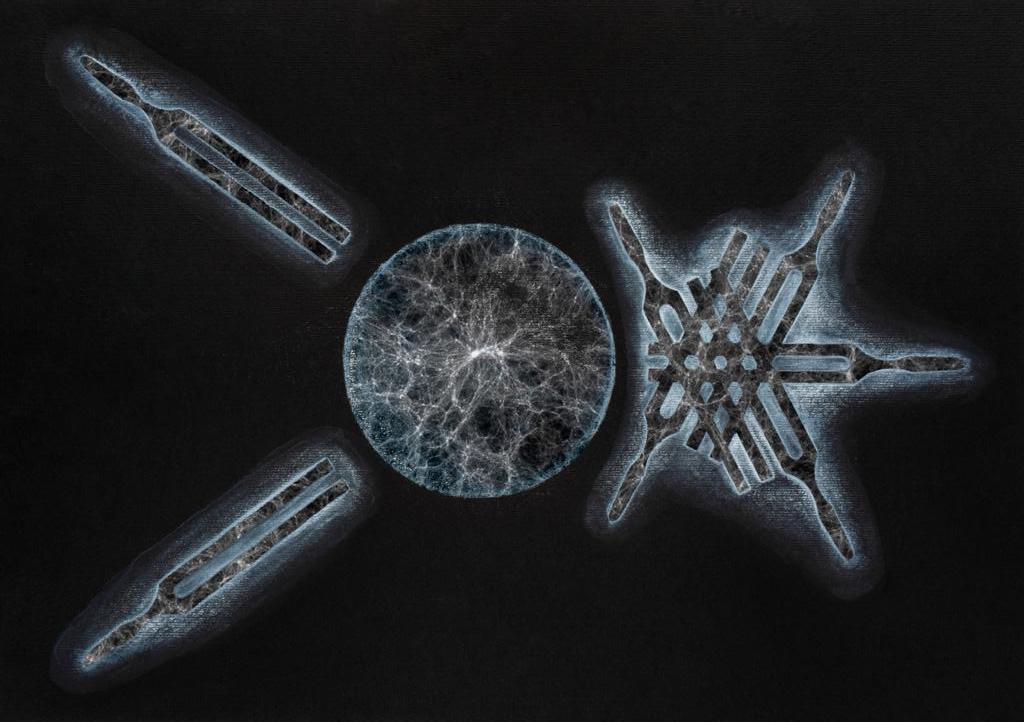

Polymorphic Microbe Bodies: Multisensory Somatic Workshop

Erin Robinsong and Hanna Sybille Müller

Polymorphic Microbe Bodies is a multisensory dance work created by Hanna Sybille Müller and Erin Robinsong that invites audiences on a somatic journey into their own bodies. Guided by binaural sound, smell, touch, language and taste, we travel the microbial worlds inside our mouths, guts and imaginaries. More than half the cells in our bodies are not human but microbial, and we are like planets, composed of ecosystems, inhabitants and relationships. Bacteria, viruses, archaea and fungi together form ‘our’ body. What does it mean to be a multispecies community? How do we feel our multiplicity?

NOTE: Participants must bring their own headphones and smartphone to access the binaural sound file via a QR code.

ARTISTS SHORT FILMS

Eglė Budvytytė in collaboration with Marija Olšauskaitė and Julija Lukas Steponaitytė, Songs from the compost: mutating bodies, imploding stars, 2020

Songs from the compost is a hypnotic exploration of nonhuman forms of consciousness and different dimensions of symbiotic life: interdependence, surrender, death, and decay. The song lyrics draw on the work and words of biologist Lynn Margulis, celebrating the role of bacteria in making life and the collaboration between the single-cell organisms possible, as well as concepts by the science-fiction author Octavia Butler, who employed tropes of symbiosis, mutation, and hybridity to challenge hierarchies and categorisation.

Kyriaki Goni, A way of resisting (Athens Data Garden), 2020

An imaginary community of digital citizens stores its most valuable digital data in micromeria acropolitana – a small plant that is endemic to the Acropolis. The life cycle of data follows that of a plant, fostering a relation of interdependence and care. In a peculiar garden, users become the plants’ gardeners, whereas plants in their turn become gardeners of the stored information. Can anyone think of the future of connectivity beyond surveillance, minimising the consequences of technological infrastructures on the natural environment? Is it possible for the bond between human and non-human worlds on this planet to be substituted?

Asad Raza, Ge, 2020-ongoing

The first iteration of Ge, an endless and evolving video work, mixes fiction and documentary to create a portrait of the bioscape surrounding James Lovelock’s Dorset home: the conditions that produced the idea of the planet as a living feedback loop. The second iteration features the artist and his daughter demonstrating how to make soil from sand, vegetable matter and other ingredients. The third iteration traces a sailing trip with seven musicians across Lake Erie, and a subsequent performance of music they made on the voyage, in collaboration with the lake.

Ben Rivers, Urth, 2016

Urth was filmed in and around Biosphere 2, the largest closed ecological system ever created for scientific research in the Arizona desert, designed to emulate Earth’s environment (Biosphere 1). Taking its title from the Old Norse word suggesting the twisted threads of fate, Urth forms a cinematic meditation on ambitious experiments, constructed environments, visions of the future and humankind’s relationship with the natural world. An unnamed protagonist, who appears to be the last survivor of her kind, reflects upon her own mortality and the unknowable fate of the planet after the end of humanity.

Mariana Sanchez Salvador and Rain Wu, As Above, So Below, 2020

Empathy begins with acknowledging the position of our body in the world, not simply towards a different body, but also across time and dimensions. Food spans across all aspects of our lives, from the most profane everyday nourishment to the sacrifices that made an anthropological imprint on the collective psyche. It connects science and myth, known and unknown. The meal, the settlement, the landscape, the cosmos, down to the microbial and viral in our guts and in the air—food allows us to discover a new perspective on our world. The film makes use of archive images and microscopic photography of edible substances—fruits, vegetables, grain, fish, vitamins—as a metaphor of the macro, to create a timeless, scaleless world.

Jenna Sutela, Holobiont, 2022

Holobiont considers the idea of embodied cognition on a planetary scale, featuring a zoom from outer space to inside the gut. It documents Planetary Protection rituals at the European Space Agency and explores extremophilic bacteria in fermented foods as possible distributors of life between the stars. Bacillus subtilis, the nattō bacterium, plays a leading role. The term ’holobiont’ stands for an entity made of many species, all inseparably linked in their ecology and evolution.

AR INSTALLATION

Bloom, Sammy Lee, 2023

Approximately 3.4 billion years ago, Earth experienced a profound transformation. In this volatile oceanic world, water, carbon dioxide and volcanic eruptions cycled through chaotic movements of thermodynamic energy. From this chaos,a random fusion of water, enzymes, and gasses organised into a primordial cell. This single, slime-encased cell, and its multiplication, led to the rise of oxygen and the transformation of the entire planet: from below, so above.

This extraordinary chain of events set the stage for the Gaia theory, first proposed by atmospheric scientist James Lovelock and developed with microbiologist Lynn Margulis in the 1970s. Describing a living earth – a self-regulating planetary system – Gaia theory was modeled by Lovelock and Andrew Watson’s 1983 simple computer simulation, Daisy World. This black-and-white daisy-filled world illustrated temperature regulation through the feedback mechanisms of the two different types of daisies interacting with the ‘Sun’. When there was more heat, white daisies proliferated to reflect the heat away from the surface of Daisy World and cool the planet; when there was less, black daisies proliferated over white daisies to absorb more heat and warm the planet.

Bloom, like Daisy World, is a Gaian planet. In this blue oceanic world, algae bloom in vibrant colours that respond to the energy of a simulated star to effect planetary cooling, producing a sulphur-dense atmosphere. This complex simulated world responds to Dorion Sagan’s description of Gaia in his new introduction to Gaia and Philosophy (Ignota, 2023) as less ‘a reactive, cybernetic system, but rather an anticipative, autopoietic one. Autopoiesis (auto: ‘self’; poiesis: ‘making’) refers to a system – living matter – that is self-reflexive, self-oriented, literally self-producing.’ Bloom’s autopoetic simulation, a microcosm on a planetary scale, takes place in augmented reality across mixed physical and digital ecosystems to invite reflection on the entanglement of multiple systems and hybrid environments.

POETRY READINGS

Pratyusha, Nisha Ramayya and Erin Robinsong close the programme with readings engaging with entanglement, care and ecology.

This event is curated by Sarah Shin, co-founder of Ignota Books, in collaboration with Gaia Art Foundation and Science Gallery London. Media Partner: Tank. Image credit: Asad Raza, still from Ge, 2020-ongoing.

Air Age Blueprint: K Allado-McDowell and Erik Davis in Conversation

3 February 2023 at the The Berkeley Alembic.

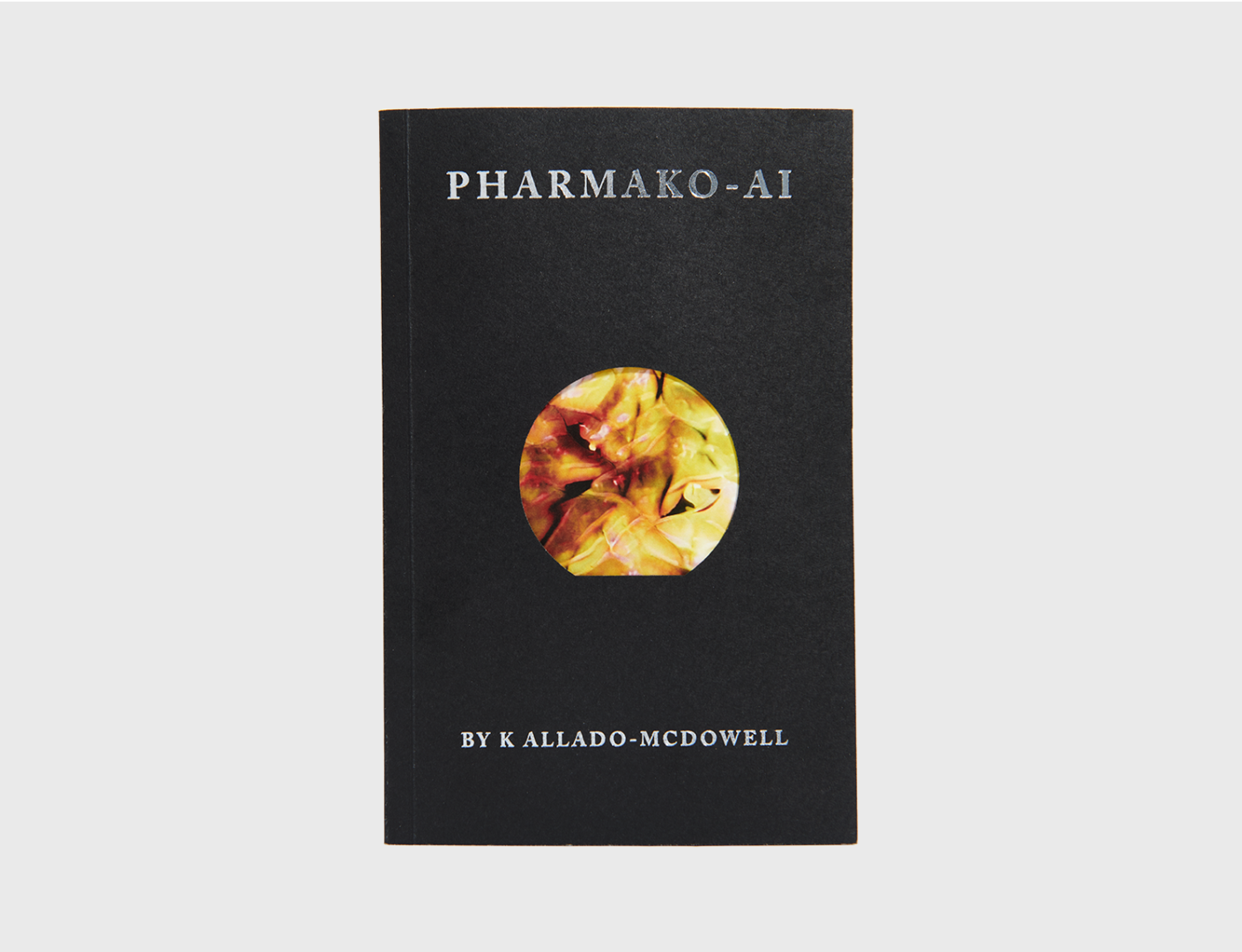

K Allado-McDowell reads from Air Age Blueprint, co-written with GPT-3. A speculative tale of a California filmmaker who encounters the world of Peruvian shamanism, the book is a fascinating follow-up to 2021’s oracular Pharmako-AI, which was the first book published in collaboration with the large language model.

Allado-McDowell, who established the Artists + Machine Intelligence program at Google AI, is joined by author and Alembic co-founder Erik Davis for a conversation on human-machine poesis, entheogenic futurism and technological animism.

Gaia and Philosophy

By Dorion Sagan and Lynn Margulis

Illustrations by Anicka Yi

In the 1970s, microbiologist Lynn Margulis and atmospheric chemist James Lovelock developed the Gaia theory. Embracing the circular logic of life and engineering systems, the Gaia theory states that Earth is a self-regulating complex system in which life interacts with and eventually becomes its own environment.

Gaia describes a living Earth: a body in the form of a planet. For billions of years, life has created an environment conducive to its continuation, influencing the physical attributes of Earth on a planetary scale. An idea with precedents in natural science and philosophy for millennia, Gaia resonates with the ancient magico-religious understanding that all is one: as above, so below. Fusing science, mathematics, philosophy, ecology and mythology, Gaia and Philosophy, with a new introduction by Dorion Sagan, challenges Western anthropocentrism to propose a symbiotic planet. In its striking philosophical conclusion, the revolutionary Gaia paradigm holds important implications not only for understanding life’s past but for shaping its future.

The Universe Listens to Us as We Listen to It

7 January 2023, 19:00

Cafe OTO, 18-22 Ashwin St, London E8 3DL

As above, so below. The Mountain rises above The Garden. As you set out, the way appears to the crown, where heaven meets earth. Your journey is accompanied by the sounds of The Mountain. The universe listens to us as we listen to it.

Ignota hosts an evening of sonic exploration, ambient resonance and abyssal sounds with. The Universe Listens to Us As We Listen to It is part of Ignota’s QUANTUM LISTENING season of events inspired by Pauline Oliveros that explore the roots and legacies of Deep Listening® with a broad curiosity toward vibration, resonance and altered states.

The evening will unfold through listening sessions, meditative performances, hypnotic journeys and expanded consciousness with special guests: Anna Wall and Susanna Davies-Crook collaborate on a hypnotic journey; Bones Tan Jones makes a vocal offering; Lawrence Lek presents an interdimensional journey through Nepenthe and the voices of artificial others; Lia Mice performs the Chaos Bells, with more performances and offerings by Maxwell Sterling and Ignota friends and family.

Anna Wall presents a brand new track continuing the ambient exploration of her Dream Theory label, which focuses on healing sonics, ambient and experimental music. Here she collaborates with Ignota’s Susanna Davies-Crook on a hypnotic journey.

Bones Tan Jones will make a vocal offering.

Lia Mice will perform the Chaos Bells, her self-designed instrument that features twenty gesturally performed pendulums. Chaos Bells is named after its unique sound design in which bell sounds can drone and become chaotic is how it gained its name.

Lawrence Lek opens a portal to his virtual worlds of listening and disembodied wanderings. He presents an interdimensional journey through Nepenthe, and grants us access to his ongoing series of sonic and visual landscapes, each centred around the voice of an artificial other.

The Universe Listens to Us As We Listen to It celebrates the launch of Ignota’s new membership portal The Mountain: a platform for aural exploration and sonic content including poetry, music, weird tech, ritual and practice.

Quantum Listening by Pauline Oliveros (Ignota, 2022) is a manifesto for listening as activism. Through simple yet profound exercises, Oliveros shows how Deep Listening is the foundation for a radically transformed social matrix: one in which compassion and peace form the basis for our actions in the world.

Caves, Dwelling & Vibration

10 – 11 December 2022 at Nottingham Contemporary

A sensorial exchange across research, mediation and performance in response to the exhibition Hollow Earth: Art, Caves & The Subterranean Imaginary. The show highlights Nottingham’s extraordinary condition as a city built on a network of caves – being the UK’s largest network over 800 hidden beneath. Caves, Dwelling & Vibration aspires to look closely into the poetic and artistic knowledge and wisdom caves carry, to deepen and complexify our understanding of geologic and deep time, archaeo-acoustics and the uses of caves as spaces of dwellings but also as spaces of upheaval.

The programme includes contributions by Laura Emsley, Ella Finer, Louis Henderson, Emma McCormick-Goodhart, Frances Morgan, Flora Parrott, Frank Pearson and Kathryn Yusoff among others. The programme is curated by Canan Batur, assisted by Philippa Douglas.

Each day ends with listening sessions and sonic meditations inspired by the work of Pauline Oliveros and the publication Quantum Listening (Ignota Books 2022). Performances by Evan Ifekoya, Paul Purgas and Lucy Railton will unfold in The City of Caves, underneath Nottingham Contemporary.

This event is programmed in collaboration with Canan Batur and Susanna Davies-Crook of Ignota Books. It forms part of Ignota’s QUANTUM LISTENING season of events that will explore the roots and legacies of Deep Listening™ with a broad curiosity toward vibration, resonance and altered states.

Image: Lydia Ourahmane, Tassili, 2022, excerpt. 4K video, 16mm transferred to video, digital animation, sound. Courtesy: Lydia Ourahmane.

Quantum Listening Launch

15 November 2022, 19:00

Reference Point, 2 Arundel St, Temple, London WC2R 3DA

Does sound have consciousness? Can you imagine listening beyond the edge of your own imagination?

Celebrate the launch of pioneering musician Pauline Oliveros’ Quantum Listening with Ignota Books at Reference Point. This marks the first in our QUANTUM LISTENING season of events that will explore the roots and legacies of Deep Listening™ with a broad curiosity toward vibration, resonance and altered states.

Join us for an evening of sonic meditation, ambient resonance and abyssal sounds with artist Aura Satz, curator and writer Irene Revell and NTS creative director Tabitha Thorlu-Bangura, hosted by Ignota’s Sarah Shin and Susanna Davies-Crook.

Quantum Listening is a manifesto for listening as activism. Through simple yet profound exercises, Oliveros shows how Deep Listening is the foundation for a radically transformed social matrix: one in which compassion and peace form the basis for our actions in the world.

Spooky Action at a Distance

29 October 2022, 19:00

Mimosa House, 47 Theobalds Rd, London WC1X 8SP

Ignota is four years old! As the veil draws thin, join us to welcome the darker half of the year and to celebrate our birthday on 29 October at Mimosa House with an evening exploring quantum spookiness, haunted synchronicities, slimy entanglements and altered states of consciousness.

In the so-called ‘normal’, observable world, everything might appear to be either a wave or a particle. But if we alter our means of perception, everything is always both. As the air age unfolds, Ignota draws inspiration from quantum theories about the inevitability of relation to look towards a more hopeful, more magical paradigm for collectivity, interrelationship and healing, even and especially in moments of complexity and chaos.

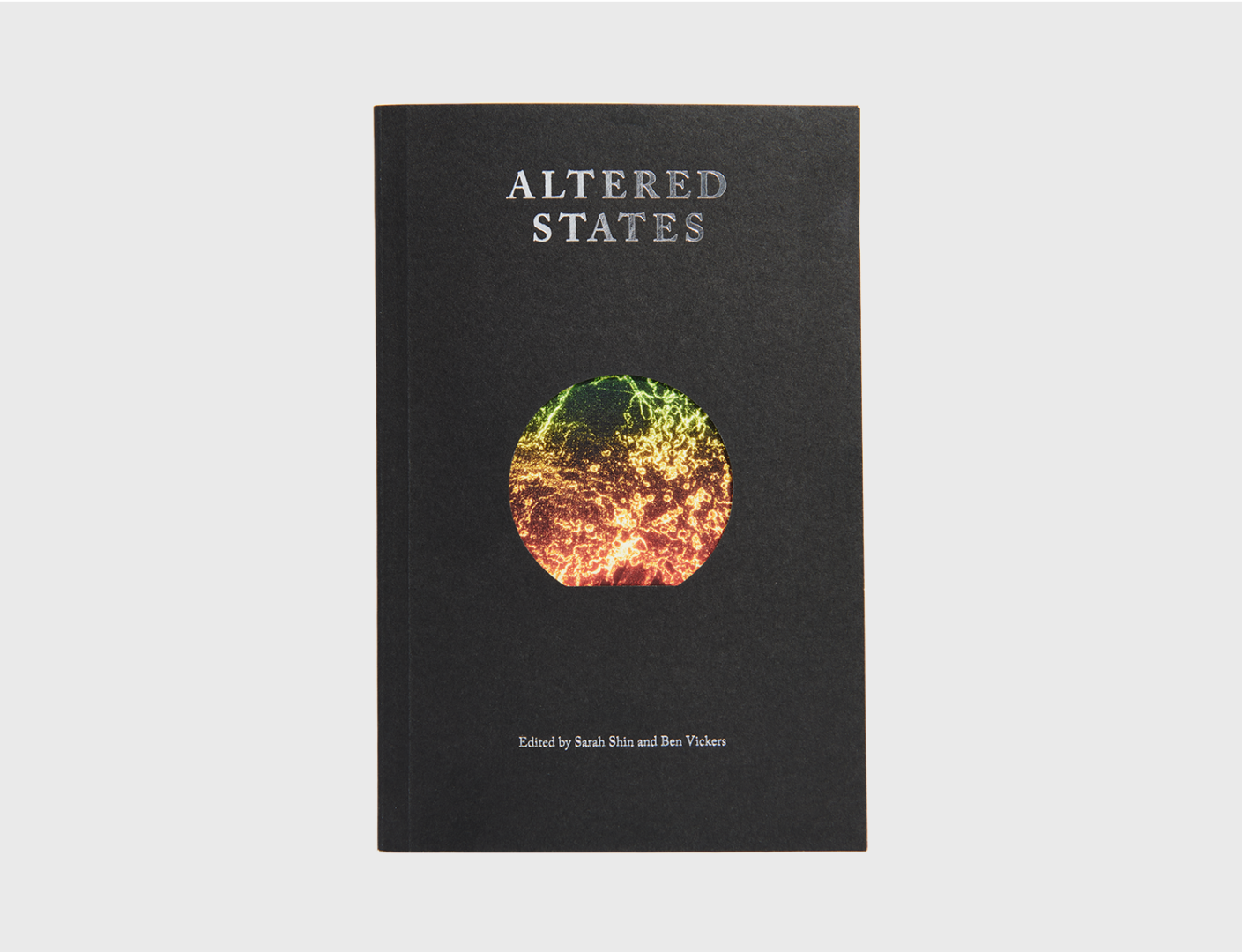

This event featured readings, practices, dreams and questions: Dreaming with the Hag – a dream invocation and incubation with IONE; an Altered States mini-launch with poets So Mayer and James Goodwin and Ignota’s Sarah Shin; a yarn entanglement ritual with healer Leila Sadeghee; a hypnotic journey through illuminating visions led by the mind’s eye with Ignota’s Susanna Davies-Crook; and a slimy performance lecture by artist and quantum physicist Libby Heaney: a slippery stream-of-consciousness travelling through quantum phenomena including sticky entanglements, many-sided superposition, slime and nature, set to a layered video montage edited with ’spooky action at a distance’ data from IBMs quantum computers.

Air Age Blueprint Longsleeve

Celebrating the launch of Air Age Blueprint , weaving fiction, memoir, theory and travelogue into an animist cybernetics – an air age blueprint – this 100% cotton, jersey knit longsleeve features artwork by Somnath Bhatt.

Celebrating the launch of Air Age Blueprint , weaving fiction, memoir, theory and travelogue into an animist cybernetics – an air age blueprint – this 100% cotton, jersey knit longsleeve features artwork by Somnath Bhatt.

- 100% cotton, preshrunk jersey knit, 203gsm

- Classic fit

- Ribbed collar

- Taped neck and shoulders

- Cuffed sleeves.

- Tubular body.

- Twin needle neck and hem

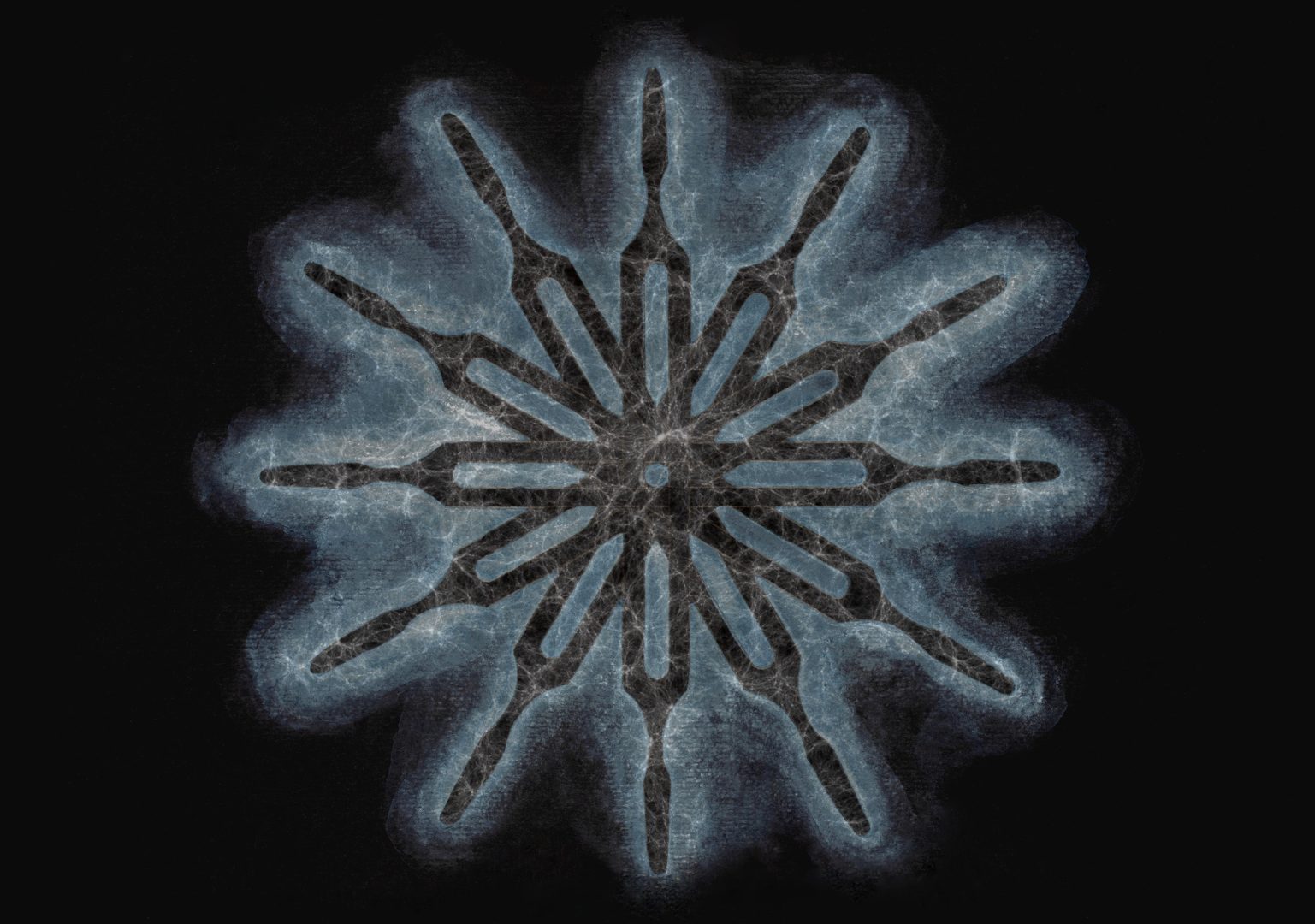

Aura Satz Edition: ‘Tuning Fork Spell’

Aura Satz’s Tuning Fork Spell translates the artist's exploration of sound, music, and listening practices into a numinous, mandalic image created for the publication ofQuantum Listening. Tuning Fork Spell is a limited edition C-type print on paper, 297 x 420mm, in a signed edition of only 50.

Find the Others Tote

This robust and substantial 250gsm 100% cotton canvas is a bag for life with a 10cm bottom gusset.

This robust and substantial 250gsm 100% cotton canvas is a bag for life with a 10cm bottom gusset.Seeds

Edited by Sarah Shin, Jay Drinkall and Marleen Boschen

Designed by Virgil Taylor

Seeds was the companion book to Ignota’s project Memory Garden at the Biennale Gherdëina, Italy, 2022. Seeds features a series of plant rituals compiled by Rasheeqa Ahmad (Hedge Herbs), Elsa Cristofolini Hamaz and Paige Emery to accompany each of the four phases of the moon, as well as texts by Lynn Margulis and Etel Adnan.Air Age Blueprint

By K Allado-McDowell

A young filmmaker’s life is disrupted by a fated encounter with a Peruvian healer. Called to twin paths of artistic creation and mystic truth-seeking, they set out on a transcontinental journey. In the Pacific Northwest they meet K, a double agent working between art and technology, who invites them to test a secret program called Shaman.AI. This human-machine experiment, rooted in magic, produces a key to rewriting reality – a manifesto describing how entangled human and non-human intelligence will remake our technologies, identities and deepest beliefs. Allado-McDowell (along with their AI writing partner GPT-3) weave fiction, memoir, theory and travelogue into an animist cybernetics – an air age blueprint. Cover art by Somnath Bhatt.Quantum Listening Event: Pauline Oliveros at 90

Hosted by Ignota and Gray Area on 10 August 2022

IONE, Laurie Anderson, Morton Subotnick, Aura Satz, members of the San Francisco Tape Music Center and Center for Contemporary Music and many more celebrate Pauline Oliveros’ life and work. IONE leads a Sonic Meditation which will be followed by reflections and remembrances from friends of Pauline.

In response to the anti-war movements of the 1960s, pioneering musician and composer Pauline Oliveros began to expand the way she made music, experimenting with meditation, movement and activism in her compositions. Fascinated by the role that sound and consciousness play in our daily lives, Oliveros developed a series of Sonic Meditations that would eventually lead to the creation of Deep Listening. In Quantum Listening, Oliveros shows how Deep Listening is the foundation for a radically transformed social matrix: one in which compassion and peace form the basis for our actions in the world.

Flower and Flame: Beltane Ritual Writing workshop with Pam Grossman & Janaka Stucky

Beltane is celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Falling opposite Samhain on the wheel of the year, it is one of two annual moments when the veil between worlds is thinnest and spirits may make their presence known.

In this workshop, word witch Pam Grossman and occult poet Janaka Stucky guided rituals and exercises to work with the generative energies of Beltane, supportive of creativity and fertility in all their forms. To invite in a new season of promise, we worked with spring deities, magic gestures and mystical writing techniques to unfurl floral and plant incantations and welcome fiery, divine inspiration.

Image: ‘The Worker’s May-Pole’ by Walter Crane (1894)

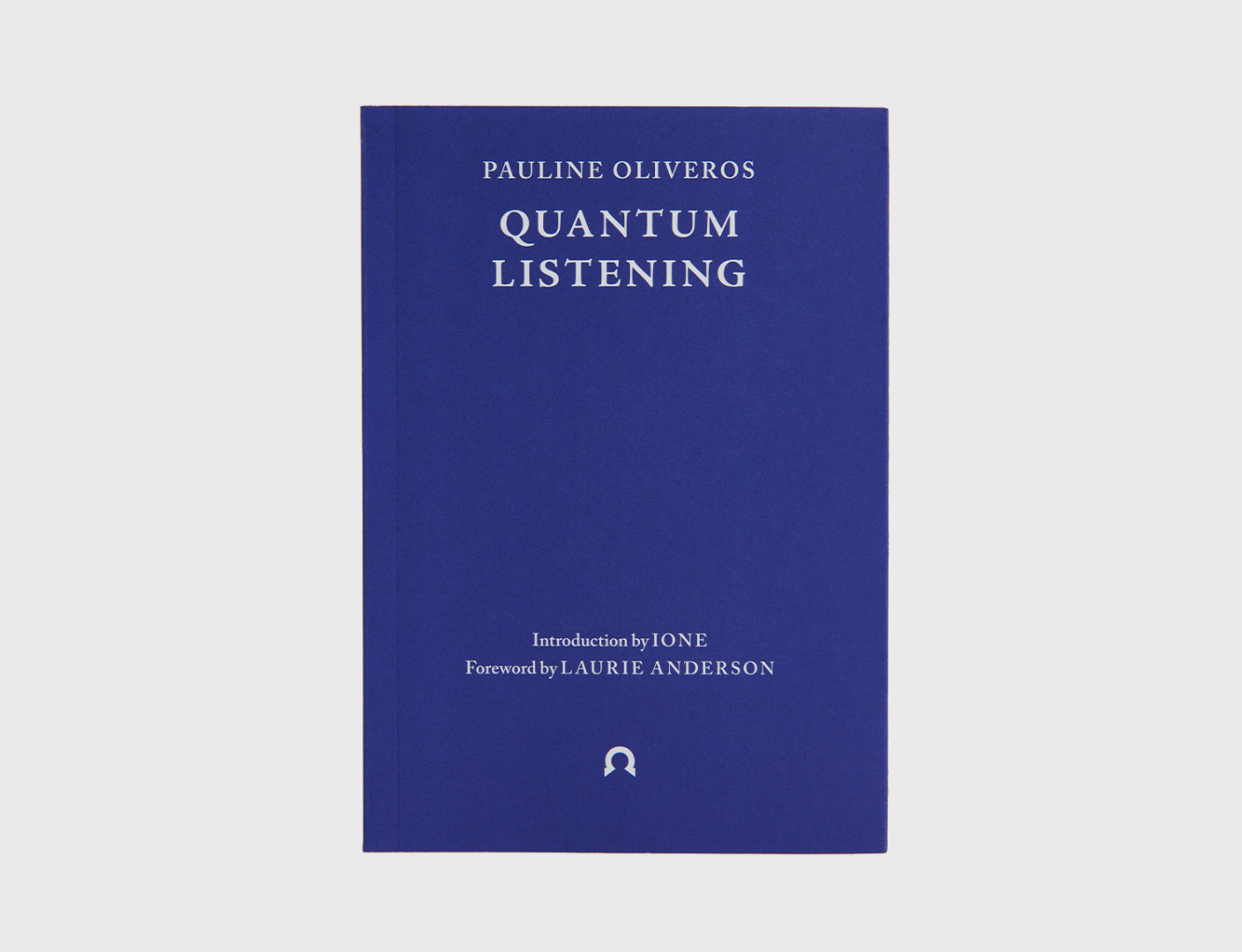

Quantum Listening

Introduction by IONE

Foreword by Laurie Anderson

Illustrations by Aura Satz

What is the difference between hearing and listening? Does sound have consciousness? Can you imagine listening beyond the edge of your own imagination?

In response to the anti-war movements of the 1960s, pioneering musician and composer Pauline Oliveros began to expand the way she made music, experimenting with meditation, movement and activism in her compositions. Fascinated by the role that sound and consciousness play in our daily lives, Oliveros developed a series of Sonic Meditations that would eventually lead to the creation of Deep Listening – a practice for healing and transformation open to all, rooted in her musicianship.

Quantum Listening is a manifesto for listening as activism. Through simple yet profound exercises, Oliveros shows how Deep Listening is the foundation for a radically transformed social matrix: one in which compassion and peace form the basis for our actions in the world.

This timely edition brings Oliveros’ futuristic vision – blending technology and spirituality – together with a new Foreword and Introduction by Laurie Anderson and IONE.Worlding: Flavie Audi and Aliya Say – Other Worlds

On 17 March 2022, Ignota hosted artist Flavie Audi and art writer and researcher Aliya Say for the final event in Ignota’s Worlding series.

What are other worlds? How is the invisible made visible, felt and sensed? Why has humanity throughout history been drawn to divine otherworldly realms and experiences? And what forms and shapes can the divine take in the contemporary context? In conversation through the form of a visual essay, Flavie Audi and Aliya Say explore tools and approaches that have been used to access, visualise and narrate spirit realms by artists such as Hilma af Klint, and in their own speculative practices looking towards the future and more than human ontologies.

Worlding: Alice Bucknell – Aquaform, Terraform, Aeroform: Worlding the Interplanetary

On 10 March 2022, Ignota hosted Alice Bucknell in the Worlding series.

For millennia, Mars has saturated public imagination with alternative worlds, fantastical ecosystems home to high-tech canal cities, cephalopod dwellers, and communist utopias. But as our image of the Red Planet pivots increasingly towards that of a site for human habitation and resource extraction – with billionaire tech despots at the helm – how can worlding help us envision the many possible futures for Mars, as a host for both human and nonhuman life? What are the legal, political, ecological, and existential frameworks in which these worlds could take shape?

Drawing on speculative fiction strategies, as well as materials science, linguistics, space law, and prophetic applications of AI, artist Alice Bucknell explored a trifecta of possible Martian worlds, from a bio-infrastructure business vending clean water and air back to Earth, to a mystic cult of plant worshippers auguring ancient polyglot ecologies on the Red Planet. Bucknell took us behind the scenes of interplanetary worlding processes, including collaborations with space lawyers, arctic researchers, Scottish drone pilots, NLP specialists, and the Language AI GPT-3.

All proceeds were donated to Africans in Ukraine, an organisation helping African students and other Black individuals in Ukraine secure safe passage out of the country.

Worlding: Amelia Winger-Bearskin – SKY WORLD/CLOUD WORLD

On 20 January 2022, Ignota hosted Amelia Winger-Bearskin in the Worlding series.

Artist Amelia Winger-Bearskin gives an illustrated lecture about her project SKY WORLD/CLOUD WORLD, which examines the sacred nature of our ’cloud’-based communications.

SKY WORLD/CLOUD WORLD tries to understand ‘the cloud’ as both a spiritual place and a vehicle for the ephemeral way in which we choose to communicate with our kin over distance and time. This concept of the cloud in web-based applications has interrupted our notion of a SKY WORLD/CLOUD WORLD which is the grand connective tissue all humans have with one another. We must maintain and honour our SKY WORLD/CLOUD WORLD, the layer of sky which protects our world, maintains our atmosphere, and which has given us the ability to communicate through invisible signals through satellites, tubes and more importantly through dreams and imagination.

Worlding: SJ Anderson – Astrology and the Architecture of Time

On 6 January 2022, Ignota hosted SJ Anderson for the first in the Worlding series.

Astrology is a form of world-making through witnessing and interpreting the measurements of the movements of celestial bodies in the night sky. These interpretations form meaningful narratives, which can assist practitioners in making sense of their lives.

SJ Anderson and Sarah Shin discuss astrology as the architecture of time and a guide to navigating cycles of rebirth and crisis. Collective crisis is often a necessary condition for a new world to be born: how does astrology give meaning to worlds in flux? SJ looks ahead to the astrology of 2022 in the context of various planetary cycles, including the Barbault Planetary Cyclic Index, which predicted a pandemic in 2020, and outer planets such as Neptune.

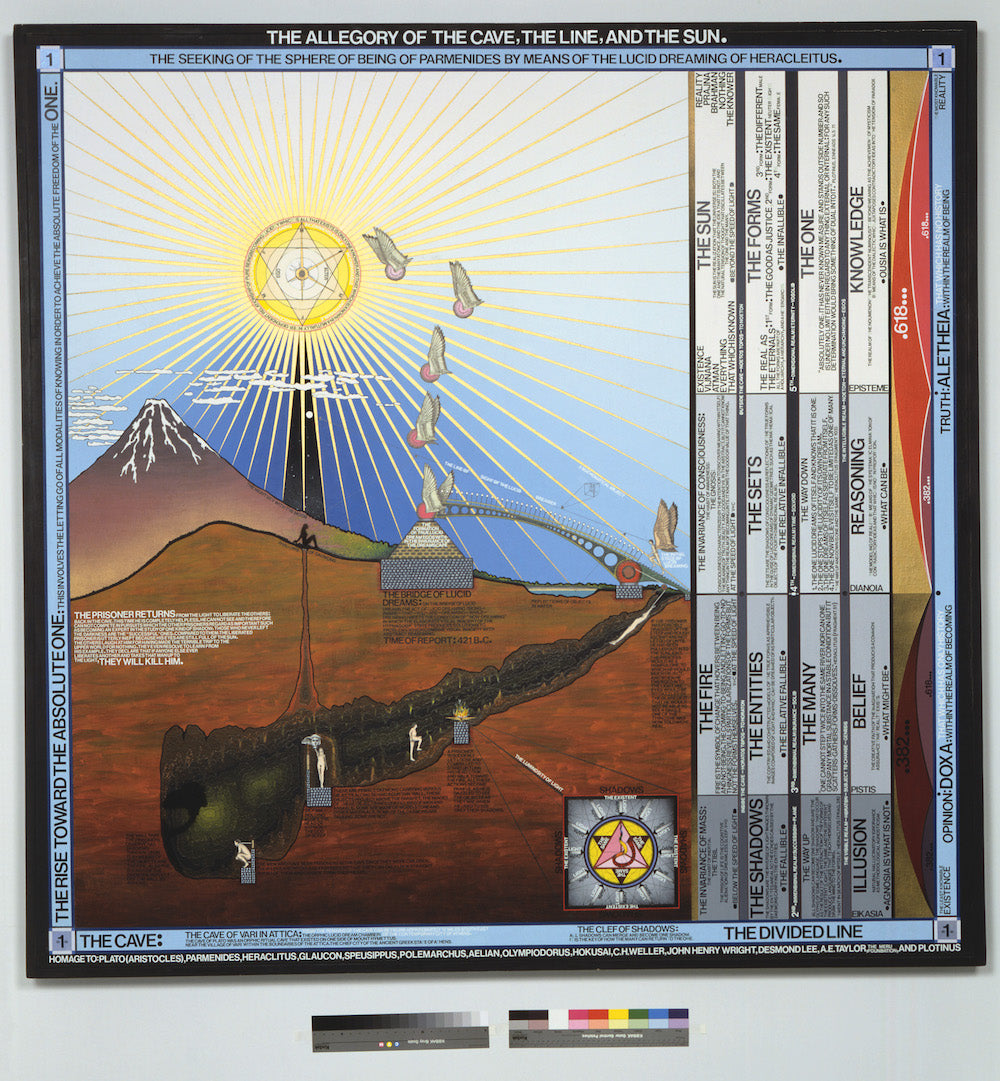

Worlding: John Tresch – Cosmograms, or How To Do Things with Worlds

On 17 February 2022, Ignota hosted John Tresch in the Worlding series.

All cultures have composed and deployed representations of everything that is – cosmograms – to convey the fundamental entities, relations and processes that make up the universe.

Studying cosmograms as pictures, sculptures, books, rituals, buildings, cities and so on is a way to compare worlds – their components, histories, aesthetics and modes of being – as they are proposed, debated and imposed: as they come together and fall apart.

In this talk, John Tresch draws from a forthcoming book looking at the creation and impact of scientific cosmograms alongside those of religion, myth and art.

Worlding: Reza Negarestani – We do not need to be saved from a world we could have: of worlds and humans

On 3 February, Ignota hosted Reza Negarestani in the Worlding series.

Neither entirely philosophical nor fully science-fictional, this presentation by philosopher Reza Negarestani seeks to define what it means to live in or inhabit a world, all things considered. Its title refers to Christopher Nolan’s latest movie Tenet, in which the protagonists flaunt their time-policing powers of saving us from a different world we could have.

By virtue of living in a world, one has, also, the wherewithal to think about what else could have happened. Eventually, one arrives at an ethical and communist responsibility to travel to the past to postulate and exemplify what sort of worlds and humans we could have, and which the time cops’ narratives deprive us of.

Ignota Hosts: ‘Prophetic Culture’ Book Launch

On 3 June 2021, Ignota welcomes Federico Campagna for a special lecture to celebrate the launch of his book Prophetic Culture: Recreation for Adolescents (Bloomsbury 2021).

In this book launch, he explores ‘Cosmography’, the third and final part of the book – a metaphysical journey across the dimensions making up reality, retold in a style that combines the tones of epic, romance and fiction for young adults.

Throughout history, different civilisations have given rise to many alternative worlds. Each of them was the enactment of a unique story about the structure of reality, the rhythm of time and the range of what it is possible to think and to do in the course of a life. Cosmological stories, however, are fragile things. As soon as they lose their ring of truth and their significance for living, the worlds that they brought into existence disintegrate. New and alien worlds emerge from their ruins. In Prophetic Culture, Campagna explores the twilight of our contemporary notion of reality, and the fading of the cosmological story that belonged to the civilisation of Westernised Modernity. How are we to face the challenge of leaving a fertile cultural legacy to those who will come after the end of our future? How can we help the creation of new worlds, out of the ruins of our own? As part of this event, Federico also presents for the first time the earliest work-in-progress of his next publication, which will be centred on the practice of cultural syncretism.

The Lake Before the Sun Was Born: Abolition and Solidarity

Departing from the exhibition Amaru’s Tongue: Daughter and its underpinning by the Aymara nation’s abolitionist traditions and their inseparability from Black radical traditions, this event featured curator and educator Thiago De Paula Souza in conversation with anarcho-feminist collective Mujeres Creando and writer, DJ and cultural producer Sonia M. Garcia. The conversation expanded on solidarity among Indigenous and Black people and other groups who experience oppression under colonial legacies across the world, and abolition in relation to their respective practices as curators, researchers and activists.

Programmed by Ignota Books and Auto Italia in cooperation with NTS Radio and held 2-4 November 2021. This programme was made possible with the support of Goethe Institut London and Canada House. All profits from tickets were donated to Land In Our Names, a grassroots Black-led collective committed to reparations in Britain by connecting land and climate justice with racial justice.

Ignota Hosts: ‘The Tarot of Leonora Carrington’ with Susan Aberth and Tere Arcq

On 25 May 2021, the tenth anniversary of Leonora Carrington’s (1917–2011) passing into the spirit world, Ignota hosted a special event with Susan Aberth and Tere Arcq celebrating the publication of their new book The Tarot of Leonora Carrington by Fulgur Press.

While researching for Leonora Carrington: Magical Tales (2018, Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City), curator Tere Arcq discovered a Major Arcana tarot deck painted by the artist. In this illustrated talk, Tere Arcq and Susan Aberth speak about the creation of their new book and the centrality of the tarot to Carrington’s overall creative process and life, followed by a conversation with Pam Grossman, author of Waking the Witch: Reflections of Women, Magic, and Power (2019).

The Tarot of Leonora Carrington is the first book dedicated to this important aspect of the artist’s work. It includes a full-size facsimile of her newly discovered Major Arcana; an introduction from her son, Gabriel Weisz Carrington; and a richly illustrated essay from Tere Arcq and Susan Aberth that offers new insights — exploring the significance of tarot imagery within Carrington’s wider work, her many inspirations and mysterious occult sources.

The Major Arcana by Leonora Carrington (introduced by Rachel Pollack) and The Tarot of Leonora Carrington by Susan Aberth and Tere Arcq (introduced by Gabriel Weisz Carrington) are published by Fulgur Press.

Ignota Hosts: Tai Shani, ‘The Neon Hieroglyph’

‘The building of a house we will never live in – a house for our ghosts where the gothic and the hallucinatory collide.’

Tai Shani presents The Neon Hieroglyph in a special event featuring readings, a musical performance by composer Maxwell Sterling and a conversation between Shani and anthropologist Amy Hale exploring the feminised history of ergot, metaphysical and material realities and psychedelic mythos. The event is hosted by Ignota in partnership with Manchester International Festival (MIF).

Tai Shani creates worlds that are at once dark yet luminous, both feminist and fantastical – and in The Neon Hieroglyph, she constructs a story-world that draws inspiration from her research into ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains from which LSD is derived, as a psychedelic catalyst. Ergot played an important part in the North West’s agricultural, social and medical history: linked to local crops and breads, outbreaks of ergot poisoning caused mass hallucinations, with the last reported UK incident during the late 1920s in Manchester. Composed of nine short episodes and featuring a mesmeric soundtrack by Manchester-born composer-musician Maxwell Sterling, The Neon Hieroglyph uses these experiences to spark new visions and alternative realities: a dreamlike CGI journey that takes us from the cellular to the galactic, from the forests to the subterranean, from the real to the almost unimaginable.

CCA Glasgow and Ignota Hosts: ‘Soot Breath / Corpus Infinitum’

On 30 November 2021, CCA Glasgow and Ignota hosted Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva for a screening of their new film Soot Breath / Corpus Infinitum, and a discussion with James Goodwin. Soot Breath / Corpus Infinitum was accompanied by a performance of Treble Heaven by Nisha Ramayya and MJ Harding.

Soot Breath / Corpus Infinitum by artist Arjuna Neuman and philosopher Denise Ferreira da Silva continues their interest in reimagining knowledge and existence without the limits of European and Colonial constructions of the human. To speculate how to exist otherwise as humans in the world, they traverse from quantum mechanics to polyrhythms, from Tarkovsky to Hype Williams, from heat to Anaximander.

Following the element of earth through its many facets, groundings, afterlifes and forms, Soot Breath scales between the historical/cultural, the organic, the quantum and the cosmic. Gathering a variety of examples where subjectivity is unbound from the mind alone, but rebound to the world, Soot Breath examines how structures of power break material ties to other humans, more-than-humans and deeper implicated bonds with our planet and beyond.

Soot Breath / Corpus Infinitum is a film dedicated to tenderness. It reproduces a radical sensibility we learned from listening to the blues, from listening to skin, to heat, and from listening to echoes, listening itself. The film was developed with the Centre for Contemporary Art, Glasgow as a commission for the Glasgow International 2021. A newspaper was produced as part of the show with writing contributed by Nisha Ramayya.

Treble Heaven is an encounter between poetry and music by poet Nisha Ramayya and sonic dramaturg MJ Harding, exploring three ways of singing to heaven and three different types of longing. Treble Heaven is a ritual treating the damage of European and colonial cosmology and an experiment in collective gathering and releasing.

At the edge of a black hole, information is released.

Slice and glissando; drone and twinkle;

subjectivity dispersing and constellating in the forest.

The Lake Before the Sun Was Born: Herbalism and Land Ties

Writer and artist Edna Bonhomme chaired a conversation that brought together medical herbalists Sage LaPena and Rasheeqa Ahmad, with a guided ancestral meditation by multidisciplinary artist Tabita Rezaire. The talk focused on land ties, herbalism, and relations to land through ritual and lineage in the context of Indigeneity, as well as diasporic experiences shaped by broader dynamics of displacement and extraction, and ancestry, memory and repair.

Programmed by Ignota Books and Auto Italia in cooperation with NTS Radio and held 2-4 November 2021. This programme was made possible with the support of Goethe Institut London and Canada House. All profits from tickets were donated to Land In Our Names, a grassroots Black-led collective committed to reparations in Britain by connecting land and climate justice with racial justice.

Ignota Books of the Year 2021: Part II

Ignota friends and family choose their books of the year! <3 As we near the end of another challenging year, we offer this list of books and pamphlets chosen by Ignota’s friends and family, which have accompanied their journeys. Part I here.

As this list is also intended in support of the book trade, especially fellow indies, we’ve added links to Bookshop.org (which unites independent booksellers to provide an alternative to Am*zon) or directly to publishers’ websites.

Susan Aberth

The Invisible Painting: My Memoir of Leonora Carrington by Gabriel Weisz Carrington

The Ghost-Feeler: Stories of Terror and the Supernatural by Edith Wharton

Succubations & Incubations: Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud (1945-1947) by Cole Heinowitz

Jaya Klara Brekke

Anam Cara by John O’Donohue (1996, Penguin): A stunning and soothing book that keeps reminding me of the wealth that springs from the quiet. I have been re-reading it this year in an entirely new light as I have been thinking and writing and working on what a ‘digital dark’ might entail. The book speaks of the encounter with nature, with the darkness before dawn and of the importance of interiority. I recently joined a major decentralised privacy project as head of strategy. And Anam Cara, apart from calming my racing mind, is also providing a trickle of inspiration for thinking about the growing importance of privacy as almost every action and interaction is becoming digitally mediated. It is giving me some perspectives on how important it is to ensure the possibility to remain unformed, also in the digital, so that we can remain free to not make our minds up, to not have a ‘take’, to not have to maintain our exterior, and instead simply be in what I somehow imagine as the soup of emergence.

Close to the Machine,Technophilia and its Discontents by Ellen Ullman (1997/2013, Pushkin Press): What does it mean to be ‘close to the machine’? In this brief but essential book, Ullman gives us snippets and stories of life as a female software engineer just before Silicon Valley became Silicon Valley. What is incredible about reading this little book from 1997 today is that the seeds of all the big themes of contemporary digital life can be found in each of these entertaining stories. The beginnings of surveillance tech, the love for the ‘system’ over and above meatspace end-users, the cypherpunks and early dreams of anonymous digital currencies. For those of us with a foot in the world of cryptocurrencies, it is eerily familiar to read the vocabulary of one of her lovers, a young Brian, talking about arbitraging the US legal code to create an anonymous online banking system: ‘His obsession about the privacy of wealth is like my generation’s obsession about the privacy of identity, or sexuality, or belief, or the self’, Ullman writes. The book is so incredibly refreshing for her personal perspectives and off-hand commentary as she compares cypherpunks to Yippies: ‘Boys being bad, what else is new.’ As Jaron Lanier writes in the introduction to this edition: ‘...a plain account of living with computation is hard to come by.’ As opposed to science fiction, this is a lived account of ‘what it felt like when humans were first engulfed by artificial computation’, as entertaining, incredible and insightful as only ordinary life can be.

New Money: How Payment Became Social Media by Lana Swartz (2020): While walking to the east London Turkish cafe to finish writing these three snippets, I found myself squinting blurry eyed while trying to see the people across the road. I realised I had spent most of my waking hours this week glaring at my phone, then laptop, then phone again, needing these devices to satisfy nearly every task or desire, which has now affected my eyesight. This excellent book by Lana Swartz discusses money as a medium. And with that seemingly simple intellectual twist, she opens up a whole new way to consider how the particular forms that money takes have major societal effects in and of themselves. From the building of nations to the stratification and control of social classes. And, I reflected, also on our bodies, my body. This has been a go-to book for me this year for thinking through cryptocurrencies, cashlessness and central bank digital currencies, and more.

I think a new type of awareness is increasingly required in our day and age, and it is the awareness of the mediums through which things are achieved, their historical specificity, and their ‘externalities’. All too often when considering digital technologies, the focus is on what can be achieved. Instead, the focus should be on how that particular way of achieving things comes with costs: to our spirit, minds and bodies, societal relationships and, of course, environments. These three books have provided me with a ground and compass for such reflections.

Jen Calleja

Blind Spot: Exploring and Educating on Blindness by Maud Rowell is part of the 404 Inklings series of pocket-size works of non-fiction, and is a fascinating essay that sets out to correct the erasure of notable blind people in history and reveal the bias awarded the sense of sight in society and culture, including in the appreciation of art. Rowell argues in the book that accessibility should not be an afterthought in any part of life, the sciences or the arts, but rather something integral that can make it possible for blind people to live independently, work, share in experiences with friends and family, bring insight across all fields of knowledge, experience art, and flourish – all of which are fundamental for one’s sense of humanity and dignity. études by the late Austrian poet Friederike Mayröcker translated by Donna Stonecipher and published by Seagull Books a year before Mayröcker’s death is a mesmerising and mystical collection that gets closer than close to late-life consciousness through diary-entry-like poems piling up quotidian detail and idiosyncratic, almost absurdly humourous repetition. It is a whole world and in a league of its own, a feat of poetry and of translation.

Anne Duffau

This year I have been craving for more comic books to daydream and evade. I have discovered: Map to the Sun by Sloane Leong (2021), teenagers, basketball, hopes and revenge - Leong is a self taught talented writer and illustrator who creates immersive sceneries with acidic and pastels colours that will make you stick to the pages to the end.

I keep on returning to Paper Girls by Brian K. Vaughan and illustrated by Cliff Chiang, published by American company Image Comics (2015-19). The colourist is Matt Wilson, the letterer and designer is Jared K. Fletcher, and the colour flatter is Dee Cunniffe. It is a sci fi adventure set in the late 80s following four paper girls on their bikes; they encounter other teenagers who are time travellers and make a life changing discovery.

The second comic book that I cannot stop returning to is Motor Crush, another sci fi action by Authors/Illustrators: Brenden Fletcher, Babs Tarr, Cameron Stewart (2017) – Domino Swift is the main character and she is a talented motorcycle racer, she competes with gangs at night in violent bike wars.

I am impatient to read Nnedi Okorafor’s new novel: Noor which will be out on the 16th of Nov. 2021 following the character Anwuli Okwudili who calls herself: AO (Augmented Organism) and is using body augmentations to compensate for her physical and mental disabilities over the years. Set in a near-future Nigeria, she’s partially robotic and can defend herself.

Federico Campagna

You know you’re reading a great book, when halfway through it you begin to feel a surge of irrational resentment towards the author. Oh, if only I had written it! That’s precisely how I felt while reading I Miei Stupidi Intenti by Bernardo Zannoni, a 25-years old author at his first novel. It is the story of a weasel who is sold into slavery by his mother to a food-lending fox, in exchange for one and a half chicken. In winter, when starvation bites, there is no room for sentimentalisms – especially among the animals of the forest. And all the protagonists of the novel are animals; all, except two. The old fox who has taken the weasel as his own slave does not see himself as an animal. One day, years earlier, he found something in the forest that irrevocably changed his idea of himself. And the young weasel might be the only other creature in the forest who could take this gift and this burden off the fox…

Half-way between an enchanted fable, a brutal remake of a Pixar film, and a treaty on theology and violence, I Miei Stupidi Intenti deserves to be available to readers in all languages – yet, at the moment it is available only in Italian. Anglophone publishers don’t let it pass you by!

My second choice is another great book, which is as-yet unavailable in English: Theophania, by Walter Otto, originally published in German in 1956. Today, in the English-speaking world, Walter Otto is known mainly as the teacher of Karoly Kerenyi and as an influence on Martin Heidegger. But his work deserves to be rediscovered and appreciated also in its own right. This short book, written towards the end of his life, beautifully summarises the main lines of enquiry that Otto pursued throughout his life as a scholar. Theophania talks about the existential experience of reality, as disclosed by the mythological and epic texts of ancient Greece. These are not only literary works, but they are the faithful reflection of a particular way of looking at reality, which makes it possible to become aware of the ineffable, divine and archetypal forces that swarm within it. Guided by Otto’s clear and lyrical prose, the reader will learn to read the Greek classics of art and literature with entirely new eyes, and to take seriously the image of reality which they convey. This is the best piece of Pagan propaganda since the time of Julian the Apostate.

My third choice is a classic of late-ancient Mediterranean literature: The Alexander Romance. A mix of anecdotes, myths, letters, historical accounts and folk tales collected over the centuries, it hardly counts as a “book”. Rather, it is a broad narrative frame where the life and adventures of Alexander the Great are allowed to proliferate well beyond the limits imposed by history. In the Romance, Alexander’s story begins in Egypt, as the secret son of a Pharaoh-magician, and it proceeds beyond the edge of the map: in the Land of Wonders, among the giant desert-ants and the trees that vanish with daylight, in the valleys inhabited by monsters and prodigies, all the way to the complete darkness of the Land of the Blessed, which hides the secret location of the Spring of Eternal Youth. Best enjoyed together with its Arabic and Persian spin-offs (the popular Iskandarnamah and the section on Alexander in Ferdowshi’s masterful Shahnameh), the Alexander Romance is a great ancient classic that deserves to be rediscovered.

Hannah Gregory

Jackie Wang’s The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void has been assisting me in dreaming and writing deep; in not fearing the intensity of dreams, which is to say, the intensity of life. This poetry of dream translation – splinters of the unconscious brought to language – shows how an attention to our movements in dream worlds might guide us to exist differently in relation to others when wide awake.

IONE

The Heart of the World: Travels in Tibet by Ian Baker

Future of the Ancient World: Essays on the History of Consciousness by Jeremy Naydler

Dawning Moon of the Mind by Susan Brin Morrow

All We Saw by Anne Michaels

The Narrow Road to the Deep North: and Other Travel Sketches by Basho

The Dreams by Naguib Mahfouz

Comforting beside my bed – drawn upon through their bindings, receiving through time/space – they are opening in me throughout – they are journeys that I continue through night and day dream time – comforting the traveller in me.

Pam Grossman

A Helen Adam Reader, edited by Kristin Prevallet

The marvellous Helen Adam is difficult to sum up, but in short, she was a witchy Scottish poet, playwright, and collagist who moved to the states with her sister Pat, and became part of the magic circle of Robert Duncan, Jess, Jack Spicer, and other kindred American occulture makers. Many of her supernaturally-infused poems were written and performed in the ballad tradition, and her reverberating readings of her own work were, by all accounts, chilling and exhilarating. Duncan wrote of her work, "At the heart of these poems there is a compulsive beat. It is the pulse the narrative poet contrives in her art to subject the listening intelligence to the story’s spell." Her pieces are stuffed with witches, elves, ghosts, and beasts. Tarot and celestial images abound, as do gothic landscapes and chthonic gardens. From her Anne Boleyn poem, "A Swordsman From France":

For a weird that is mine,

Six Fingers! Six Fingers!

A manifest sign!

Cast off by my Lord,

With the jewels of lost magic

I’ll conjure a sword...

Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group, by Michael Duncan et al.

I’ve been a longtime fan of the visionary painter Agnes Pelton’s, so it’s been a joy witnessing the world’s recent rediscovery of her work, thanks to a traveling retrospective that kicked off at the Phoenix Art Museum in 2019. Though she only got her due posthumously, she didn’t work in isolation, as she was part of the Transcendental Painting Group which began in the 1930s. Deeply influenced by Theosophy and the mystical energy of the southwest, the TPG’s aim was to express esoteric ideas through abstract forms - and the results are nothing short of breathtaking. Another World is an extensive exhibition celebrating the TPG’s artists and their cross-pollinations, and it is currently making its way to various museums. Lucky for us, the catalog is available already, so those who would like to see this splendid work are now unbound from temporal and spatial limitations! Soon folks everywhere will be swooning over the chromatic, cosmic art of Emil Bisttram, Florence Miller Pierce, and Pelton’s other transcendent contemporaries. About time.

Darkly: Black History and America’s Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor

Every now and again, one reads something that is so insightful and impactful that one’s perspective is forever changed. Darkly is one of those books for me. Taylor writes from the perspective of a Black American woman who’s had a life-long love affair with goth culture. At first she muses on the perceived incongruities that exist in holding this allegedly dual identity - after all, isn’t there some irony in her adoration for an aesthetic that is arguably very British and very white? But as the book unfolds and constellates between the work of such tenebrously tempered artists as Siouxsie and the Banshees, Edgar Allan Poe, Toni Morrison, and Jordan Peele, she makes the case that shadowy narratives can be a balm for deep melancholy and intergenerational trauma - and that Black people are perhaps the gothest of all. It’s a brilliant examination of culture and identity, and a sharp, lyrical reminder that America truly is a haunted house.

Shoukei Matsumoto

If I were to pick a favourite English book this year, I would choose The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric.

I was deeply inspired by the question of ‘how can we become good ancestors’ in this book, which I translated into Japanese and published this year in Japan.

This book encourages us to cultivate ‘acorn brain’, or long-term thinking. which is more important in this age of extreme short-termism. As a contemporary Buddhist from Japan, I would be happy if you change the way of life so that you can become better ancestors for the future generations.

Jay Springett

My recommendations for 2021 are the books that have left me thinking about them well after closing their back covers.

The Two Antichrists by Peter Grey: A deep dive into the partnership between Jack Parsons and L. Ron Hubbard. The book is a fascinating account of their relationship and work. It includes some thought provoking and detailed original research and commentary. Concerned primarily with the lead up to (and aftermath of) the pairs’ Babalon Working of 1946. The Two Antichrists is an important work for those wrestling with the legacies of Crowley, Parsons and the OTO. It is clear that if we are to claim influence from these figures we must also stay with the trouble and reckon with the legacy of L Ron Hubbard. The two figures (antichrists) in twentieth-century culture are bound to one another in ways that are difficult to tease apart. This is a book about space magick, psychosis, and cults.

Terminal Boredom: Stories by Izumi Suzuki: I was extremely happy to read the news that Verso was bringing the collected writings of Izumi Suzuki to the English language for the first time and pre-ordered it immediately. Until this year I have only ever encountered her work through the eyes of others: either an actress through the lens, or via anecdotes and footnotes of her influence on other (mostly male) artists and writers working in late 70’s-early 80’s Japan. Terminal Boredom’s stories articulate the contemporary anxieties of the culture they were embedded in. Mass media, gender discrimination, drugs, violence, and the growing influence of technology. It is not unfair at all to say this collection is an important proto-cyberpunk book and a must-read for fans of the genre.

Ledger: Poems by Jane Hirshfield: This slow, unfolding collection of poems was a gift from a friend that arrived in the early lockdown dark of this year. A gift that was very much welcomed and enjoyed. Hirshfield’s poems are light, gestural – many have a quality of a bird riding the wind. Each poem seems to ask something of the reader: ’Here’s an idea, and here’s another, look at this, notice this, how does it make you feel?’. The poems in this collection concern themselves with a variety of topics including climate change, social justice, the plight of refugees etc. But, more importantly than the subjects of the poems themselves, the book’s central thread asks us to reconsider our relationship to the wild, the world, to other people, and how we think about ourselves.

Leila Sadeghee

This year I chose to lead a group on a pilgrimage in the way of Mary Magdalene, and in preparation I finally read the gnostic text ‘Thunder, Perfect Mind’, and was summarily blown away. I had been looking to purchase Hal Taussig’s text and writings on it for years, but was put off by the price tag (it’s out of print). I dug a little deeper and found a whole mess of translations on the internet.

I love the weirdness of the phrasing of most transmissional texts, and this one is ideal for someone looking to orient to non-dual reality, or who loves the Divine. I love the amoral choice-less imperatives of this God-poem. I love how it makes nothing wrong in a sequence of paradoxes that embrace manifestations of spiritual immaturity:

And do not turn away greatnesses in some parts from the smallnesses,

for the smallnesses are known from the greatnesses.

Mark von Schlegell

Reading goes well of late. But it’s not so easy to find surprising, well-edited, portable editions of classic literature any more. Happily I managed to pick up Dr. Jenny DiPlacidi’s Mathilda & Other Stories by Mary Shelley (Wordsworth) at Treadwell’s in London, just before travel became impossible. Blacklisted and forced to work anonymously, the author of Frankenstein nevertheless continued to write weird fiction all her days. The work is surprisingly unknown. In today’s context, Shelley’s fearless, post-Gothic, death-metal tales of possible female survival (sprinkled with science fiction) shock with relevance and clarity.

As travel resumed, I was lucky to catch Georgia Sagri’s tour for Stage of Recovery (Divided Publishing) when it passed through the Rheinland. I like how the book comes without editorial apparatus or explanation. The texts speak for themselves, raw shards of a communal, political history the writer/artist/activist has lived and critically engaged in the moment. Immediate, mournful, full of love and humor, this scrappy volume occupies the future with the just-past it can’t escape.

If I had been able to read the translation of Un-Su Kim’s first novel The Cabinet (Angry Robot) before encountering the author’s first Englished meta-noir The Plotters (HarperCollins), I wouldn't have been so surprised by the latter's later pages. I've only started this strange book, and it's even more original …

Something Other: Mary Paterson, Diana Damian Martin and Maddy Costa

‘It was generally believed,’ writes Eliot Weinberger in Angels & Saints (New Directions, 2020), ‘that angels have neither biological bodies – although they do emit a heavenly fragrance – nor are they entirely incorporeal.’ It is no surprise that this book about impossible beliefs appealed to me at a time when the world was combatting an invisible and ever-mutable threat. The philosopher C. Thi Nguyen says that although the scientific method arose from the principle that people can test ideas themselves, it has created a body of knowledge that is impossible for any individual to comprehend; instead, we must trust other people’s scholarship. In other words, we no longer live in a world structured by spirituality but we do live lives filled with belief. Weinberger’s book is a poetic compendium of centuries of thought, from the biblical to the mythical, beautifully illustrated with illuminated manuscripts (with an explanation by Mary Wellesley). It is a small flavour (a heavenly scent) of the human endeavour to make sense of the mysteries of existence.

‘I am writing also to the becoming-being that you are, the one who will face a world in ruin and undoubtedly wonder over my place in all this destruction’, writes Julietta Singh in The Breaks (Daunt Books 2021), a love letter on survival in the interstices of multiple futures and pasts. This is not only a book about what binds us together, and what climates our bodies and worlds might carry into an uncertain future, but also how tending to breaks might offer us fierce models for queer love. Singh moves with fiery beauty in the languages of relation that we carry with, in the openings that care offers, and in the knowledges that move through care and love.

Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (Serpent’s Tail, 2019) slips between the sheets of the archive to hear the lives of black womxn at the beginning of the 20th century in new ways. Refusing the contemporary and historical insistence on deprivation in both the economic and moral sense, Hartman sees instead a series of energetic attempts at different ways of living, communal, feminist and queer, predating later sexual and political liberations by several decades. What she writes about theatre – ‘a domain of collective bodies, kinaesthetic experience and gestural language’ – could be a description of the book as a whole, which brings the rhythms of jazz to its movements, felt in a resistance of linearity and objectivity. It is a powerful vision of how past and future are deeply entangled, and how visioning emerges from different capacities to listen, feel and form.

The White Review

I read a lot of sci-fi this year, and one book in particular really captured my imagination: The Hair-Carpet Weavers, by Andreas Eschbach. Written in 1995, and translated from German by Doryl Jensen, the novel begins in a universe where craftsmen dedicate their lives to weaving carpets from their wives’ hair. Their intricate designs, laboured over for thousands of hours, are sold upon completion to representatives of a mysterious and revered emperor, the proceeds of the sale used to fund the next generation of hair-carpet weavers. Where the carpets end up remains a mystery, until it's revealed that the emperor is dead, and the myriad carpets are being used as part of an astonishingly grim vendetta. The book takes on grand subjects: the fall of empire, the fate of the individual worker in the face of a gargantuan political system, the deification of ideologues, and the profound difficulty of breaking free from indoctrination. But the way in which Eschbach depicts the everyday lives and craftsmanship of the weavers themselves, the beauty, skill and futility of their labour – and the extent to which workers and their families give over their lives, hair and all, to a failed and inhumane political project – is now permanently etched onto my imagination. – Rosanna Mclaughlin

I loved reading Gina Apostol’s ultra-elaborate novel Insurrecto (2018), which is luxuriant in its prose, fully po-mo in form, and tackles a true crime of Filipino history: the 1901 Balangiga massacre, when American troops slaughtered 30,000 people on Samar Island. The novel entwines the life of Magsalin, a translator, mystery writer and cinephile from Manilla, who becomes the reluctant guide, confidante and ghostwriter of a pampered American filmmaker, Chiara Brasi, who has arrived in the region to make a film about the Balangiga massacre plus her auteur father’s attempt to shoot his own war film the Philippines in the 1970s. As the novel evolves, it spirals inwards, slipping between points in time, as Magsalin and Chiara wrestle for the authorship of this little-documented history. I love how dizzy I got. Insurrecto is itself a mystery, a mise en abyme, a dazzling puzzle, full of lush clues, doppelgangers, alternative histories, voids. – Izabella Scott

Moustache by S. Hareesh, translated from Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil in 2020, was an immense pleasure to read. Its protagonist, Vavachan, is a superhuman being whose life becomes something of an oral history, taking on mythical proportions. The novel is set in Kuttanad, Kerala, and deeply embedded in the region’s history. It springs to life the stunning lushness of Kerala, mimics the devices of local storytelling traditions, and more politically, takes on the violent particularities of caste. Vavachan has grown a large moustache, which makes him look powerful, too powerful, upsetting the sensibilities of upper-caste village folk, who begin to spin tales. Kalathil had an immense task before her, the Malayalam text is written in dialect, and often in something close to meter. But there are striking interludes as the translation shows how complex Malayalam is, how fine and hyper-specific its imagery: a character’s presence is described to be like the ‘shadow of a coconut tree in the slanting evening light’ or, like ‘a strand of scutch grass nibbled by a calf.’ Moustache is an immersive, transporting read, and a keen exploration of a remarkable language. – Skye Arundhati Thomas

Ignota Books of the Year 2021: Part I

Ignota friends and family choose their books of the year! <3 As we near the end of a challenging year, we offer this list of books and pamphlets chosen by Ignota’s friends and family, which have accompanied their journeys. Part II here.

As this list is also intended in support of the book trade, especially fellow indies, we’ve added links to Bookshop.org (which unites independent booksellers to provide an alternative to Am*zon) or directly to publishers’ websites.

Rachael Allen